In 2012 the city of Rutland in Vermont was in despair. Its police department was in chaos, neighbourhoods were engulfed in a drug epidemic, housing and infrastructure were in desperate need of attention. Racism was blatant within the police department and on the street. Homelessness and hunger were largely ignored. It was a mess.

James Baker, a long-time member of law enforcement, stepped into this disorder when he accepted the position as Chief of Police. Almost immediately tragedy struck the city of 16,000 people when a 17-year-old high school senior was run down and killed by a young man who was huffing Dust-off. Baker said that we weren’t going to arrest our way out of this.

No one saw what was coming next — the planting of seeds for a vision of change. The effort led by Baker focused on collaboration. It involved members of the police department, drug recovery agencies, housing, public works, government, recreation, mental health, social services and a determined group of local citizens. At the time few agencies were sharing information. Most were working in silos, duplicating services or leaving huge holes in the services being provided.

Korrine Rodrigue was a researcher at the University of Miami, but she was commuting from Rutland. She was looking at the impact of drugs on communities and policing. She contacted Baker and they began working on a plan for Rutland. At first Baker gathered just a few others for meetings. Then larger meetings were opened to the public. The open meetings were volatile. People were angry. The police were getting blamed for everything. Baker listened and took notes.

A strategic planner facilitated an organized community meeting. Baker took notes from that meeting too. Small groups came up with ideas. A five-year goal was established to make Rutland “one of the healthiest, safest, and happiest communities in America.”

When Baker met again with his smaller group a mission statement was created; “We work together to improve health, expand community engagement and build great neighbourhoods”. Values were added: “Collaboration for the greater good and a renewed focus on the positive – “I believe in Rutland!”. The plan was heralded under the title, Project Vision: Viable initiatives and solutions involving neighborhoods.

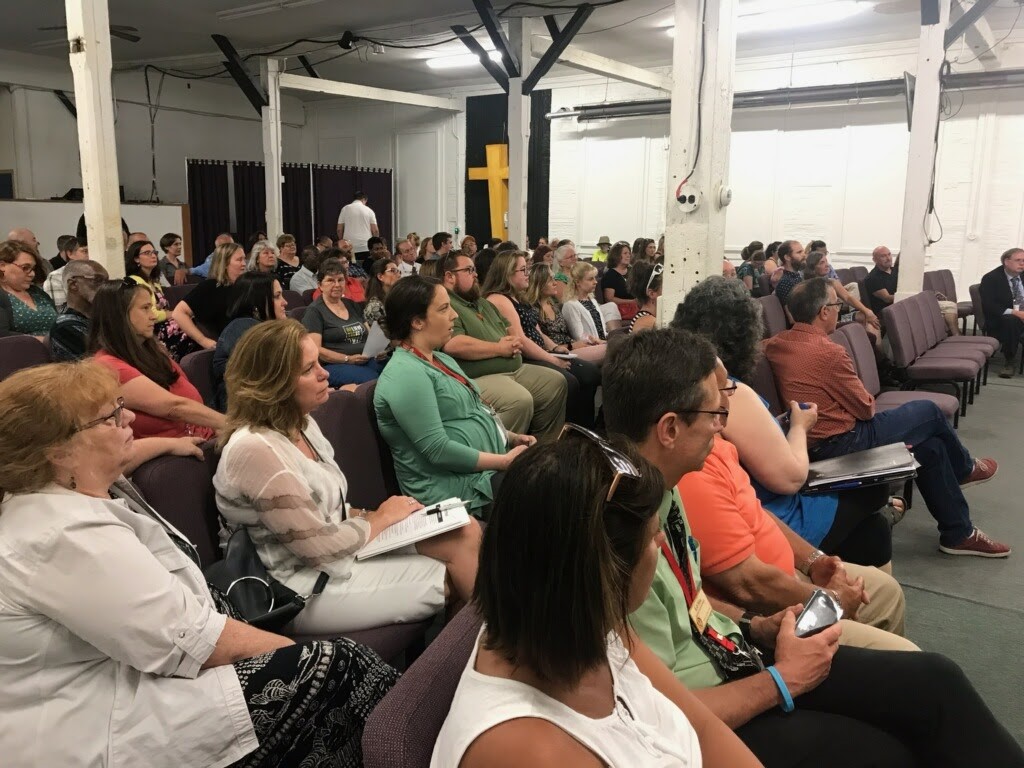

With the plan developed, more formalized monthly meetings began to emphasize “collaboration for the greater good”. People came, listened, and began to work together. Each meeting had 80 – 100 people in attendance. An outside facilitator was selected to run the meetings. Committees of volunteers were formed to address specific needs including building great neighbourhoods, crime and safety and substance abuse. Time was allotted at the end of each meeting for these sub-groups to meet. Enthusiasm was high and participants were eager to get involved. It seemed as if nothing was too big or overwhelming to try. Eventually, the groups needed more time to meet so that smaller more focused conversations could plan and implement ideas. They began to meet outside of the monthly meetings.

By 2020, after 8 years, the group still continued to meet with purpose. A recent revision of the strategic plan merged the committees into two umbrella groups to meet updated urgent needs. One was an umbrella group looking at health care that included substance abuse, mentoring youth, food insecurity, homelessness and non-opioid abuse.

The second group included engaging youth in the community, neighbourhood engagement, meeting specific needs ‘see a need, meet a need’, and community policing.

For the past four years I have conducted interviews with over 73 members of Project Vision and I researched a wide variety of agencies to understand their contributions to the community. Some takeaways from that story are listed below. Baker always said we needed to tell our own story. No one was going to do it for us.

First, the key element in all of this was breaking down the silos that separated us. Fundamental to this was the ability to listen to each other with an open mind and a willingness to try new things. “No” was not an acceptable answer to someone who came forward with an idea. It was their responsibility to put it into action.

Second, everyone agreed to adopt a renewed focus on seeing the ‘positive’ things that were happening in Rutland. Every meeting is a time of celebration.

Third, scant resources were shared as members worked together to make things happen. Competition for grant money, fundraising events and donations has largely been eliminated. Project Vision operates without a budget. The police department assigned an officer to lead the effort, but events occurred because agencies and community members joined forces and resources.

Fourth, everyone is welcome. Meetings are non-partisan. Religious, ethnic, cultural, etc. differences are left at the door.

Fifth, no one has power over other members. Participation is left up to the individual. There is no board of directors. Leadership from the Executive Director is for guidance and administration, not based on regimented rules or regulations. The only agreed upon precept was that everyone maintain civility, respect for each other and be open to each other’s ideas.

Project Vision has helped agencies to affect many changes in the city. Here are a few.

Blighted and abandoned housing has been acquired and sold, rehabilitated or torn down.

Rutland now has both a hub for administering Methadone and spoke services for individuals who do not need the tightly controlled oversight necessary for medically assisted treatment, but still need to be supervised in their recovery.

Referrals between agencies are facilitated by relationships that have been developed at and through Project Vision.

The police department is respected and welcomed in the community. Visibility through park, walk and talks along with neighbourhood walks are important ways to build trust.

Training is ongoing within the police department to improve de-escalation techniques and understanding bias. Community members have participated in some of the walks and the same trainings that the officers go through. Common experiences build bonds and positive relationships.

Rutland has both a Drug Court and Restorative Justice Center with ongoing panels to help offenders. Substance abuse is recognized as a disease. Individuals who are substance abusers and who have committed crimes because of their use of drugs or alcohol go into recovery, find jobs and often find housing. They are welcomed back into the community.

A mental health clinician is embedded in the police department to assist with calls. She goes out with a police officer and is often able to diffuse a situation before it escalates and requires an arrest.

Overdoses are down as well as burglaries which were attributed to drug abuse. Many drug houses have been replaced with single family dwellings, a children’s park, or green space. Our Sherriff’s department has a needle and drug drop-off site.

A universal release allows for better communication to help clients with varied needs. Someone can go to the hospital with a broken arm. After getting medically treated, they can be referred to homeless prevention, mental health counselling, or a recovery agency. The receiving agency can examine records that the patient wants to have shared. Doctors now have the record in front of them with drugs and visits listed so they can prescribe what is needed without conflicting with other advice or prescriptions.

Today, 2021, the effort is still strong. During COVID, Project Vision has met virtually over Zoom. Meetings continue with 80 – 100 in attendance.

Baker said that it takes leadership to “ignite fire in people’s belly.” With continued commitment from our leadership Project Vision is a long-term solution. There doesn’t seem to be any end in sight.

We Believe in Rutland: A history of Project Vision will be published later this spring. It will be available online through http://projectvisionrutland.com/.