This year’s observation of Emancipation and Independence, led to reflection on an important question which is often asked of Jamaicans. Does racism exist in Jamaica? The immediate response has often been defensive to this seemingly frightening assault on what is often perceived as national dignity. The rebuttal, which often flows effortlessly, like a well-rehearsed motto, is the assertion that we have classism not racism. What exactly does that mean? Isn’t classism the barely palatable face of racism, the dishonourable badge of honour that allows cover from distinctly uncomfortable truths. For many Jamaicans, to publicly admit that racism exists in Jamaica, creates fear of censure and social wrath and is perhaps also seen as a betrayal of country and kin. How dare one muddy the waters when our major foreign exchange earner is built on the conceptual foundation of a perfectly blended and miscegenated illusion. Yet, the effort to perpetuate this social misrepresentation, which is often conveyed to foreigners, is like sucking on a seriously sour ‘tambrin’ coated with brown sugar. The result is that it passes the first palate test until the sugar wears off. During this interchange, one is afforded the reprieve of glibly declaring ‘it’s not that sour you know,’ while one’s facial muscles are at war with one’s truth- seeking taste-buds.

Classism is no less virulent than racism for quite a number of reasons, one of which is that it has all the stealth qualities of a thief who enters your home while you are sleeping and robs you of your best jewels. This heist had its roots in slavery and its effects continue to this day. The painful fact is that for many, what has been robbed was taken so long ago and is so deeply intrinsic to their self-worth and identity, that many neither know what they have lost nor where to find it. Ask the Jamaican who has evolved from a cultural background where the tentacles of classism has encircled his social experience where his developmental mobility is stymied. Ask the Rastaman with his easily identified locks and defiance, who was and still is denigrated and ostracised, for his search and reclamation of his African roots. Ask the ‘voiceless’ Jamaican who has felt the hidden ‘whip’ of classism. That cloud that imprisons him based on his inability to skillfully navigate the English language or that deeply ingrained and hidden feeling that he was born with the wrong hue. Unravelling Jamaica’s social complexity would be a psychiatrist’s nightmare and a sociologist’s dream assignment.

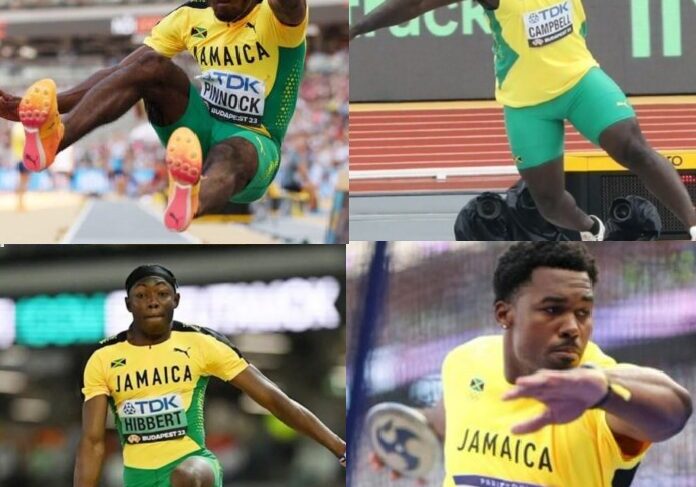

This is a society where hue or colorism is a big thing. This is clearly exemplified by the social status elevation of being regarded as a ‘browning’. Ask the ‘bleachers’ on the road and yes, in the offices. Their internal literacy and social sensitivity are so profound that they have read quite precisely the subliminal social message rooted in history, that rejects and denigrates anything ‘too black.’ Some black people also reject blackness as if it were a curse, the thief did an almost thorough job. Admittedly, saying this gives me the feeling as if I have dived into a swimming pool before looking if it has water. Interestingly and perhaps a phenomenon that should have more public discussion, is that academic education or professional status is clearly no insulation from the influence and effects of this powerful subliminal message. ‘Bleachers’ come in every form. ‘Skin Cleaning’ is not madness but a painful message, a potent cry for acceptance. This is the pain of the ‘ism’. You can attach any prefix you like, colourism, racism or classism.

While I write this, it is with the recognition of our common historical roots and its indelible influence on our society, but isn’t it too much to ask that we purposely avoid collectively addressing these realities and subsuming them under worn-out hollow platitudes. This social, historical and developmental challenge represents an amazing opportunity to better understand ourselves as a people and aids us to chart a course of personal and social evolution and acceptance. Therein perhaps, lies our social healing.

One of the most powerful endowments of language is fluent communication, the ability to speak effortlessly and enjoy the concomitant feeling of being clearly understood. With this concept in mind put yourself in the shoes of a Jamaican, who though highly intelligent, still has not mastered the illogical language of English. He still has no answer why the letter ‘H’ is not to be pronounced and at other times it must be pronounced. His primary school teacher who clearly had a similar difficulty yet as a trained teacher had integrated her brain and tongue to remember, took great care to pedantically remind him when to drop the ‘H’ as in honour and when to affix it as in the word ‘hear’. Some may remember the anecdote of the fictitious situation when a child who said to his teacher “Arry tek di ammer and it mi in mi ead” and her retort was “hemphasise yu ‘H’s, yu hignorant hass”. This simple example highlights a far deeper complex challenge in our society.

The letter ‘H’ is a powerful consonant in Jamaican society, it is one of the unspoken rules in the book of classism in Jamaica. It waits to judge its application and as surely as night follows day, classism will, if someone is found wanting, find him and categorise him, to his distinct social and economic disadvantage. One question that may well be asked, is this linguistic dilemma in a wider context, at the root of under-achievement in schools? I speak of this matter of serious import as a painful reality for many Jamaican children, yet with the awareness that this is only the tip of the iceberg. I raise this point for I have listened and seen the conflict and pain, and indeed, shame, that hides inside the supreme effort exerted by many Jamaicans to communicate in ‘standard’ English. It has led me to believe and be convinced, that standard English for many Jamaicans is not standard at all. It is my feeling that the English Language, which should be recognized for its distinct benefit as a facilitator of a wider sphere of communication, should also be regarded no differently from a foreign language in this country and should be taught as such. This is all about educational approach and attitude. No shame, no pain and social judgement should be placed on one who does not have a command of this language. But we know that this legacy of pain which has its roots in slavery, similar to a a slow acting injection into the psyche of an oppressed people, is the hidden fire that fuels this shame. The post-slavery command to be fluent in the slave-master’s language was foundational to our educational system. It inadvertently produced in many Jamaicans linguistic schizophrenia, engendered by the relentless omni-presence of the powerfully preserved Jamaican dialect.

How then can we, as a people, heal this pain? We can ignore this need for concerted action and attitudinal change, but failing this, the resultant price will be that a large segment of our population will continue to feel under-valued and oppressed. Those who are fortunate to have a command of both English and Patois, have the facility of being contextual in their social interaction

The choice is ours to embrace the reality of who we are as a people, boldly address this challenge, and recognize that we are individually and collectively on a path of continuing evolution. We can unitedly decide to refocus our efforts on our own ‘backyard’ with the will to continue to unyoke ourselves from bondage, but we certainly can’t start the process while many are still asleep. Economic reparation might be the current clarion call, ‘nuff money’ was also the bait to our enslavers who even now resolutely resist reparation. Importantly how do we wrest from the ‘thief’ our intrinsic selves as worthy descendants of a noble race.