| “If our teaching is to be an art, we must draw from all we know, feel and believe in order to create something beautiful. To teach well we do not need more techniques and strategies as much as we need a vision of what is essential. It is not the number of good ideas that turns our work into art but the selection, and balance of those ideas…writing is not only a process of recording, it is also the process of developing a story or idea. ” — Lucy Calkins The Art of Teaching Writing. Revised 1994 |

For eight years, from 2000- 2008, I was a guest lecturer in Jamaica, West Indies as part of a graduate programme at Western Carolina University in Cullowee, North Carolina. Classes enrollment was typically 60 licensed and practicing teachers coming from one region of the country at a time. I moved from place to place so that the entire island was represented. I taught in places like Mandeville, Montego Bay, Kingston, and Runaway Bay. The university arranged my accommodations and a driver, as well as the classroom facility and any materials I needed. I travelled back home to Rutland, Vermont where I stayed for months in-between classes.

Teachers in the course came after a long day of teaching for a 3-hour class, from 4:00 – 7:00 p.m. every night of the week for two weeks. Some of them travelled by minibus for up to two hours each way. I knew of students who reached home at 11:00 p.m, dealt with their families, did homework and began again early the next day with their own teaching. Others took the two weeks off so that they could devote time and energy to the programme.

It was an intensive and demanding programme. There was homework every night that included reading the text and writing journal entries. For efficiency’s sake some students prepared by reading the text in advance of the start of the course.

Because of the large enrollment, my programme had to be creative and unique. Day one I took polaroid photos of the students in groups of three and wrote their names under their picture. Then I asked them to sit alphabetically. What started as a revolt because they didn’t want their pictures taken or to have a seating arrangement that separated them from their friends, quickly subsided when I told them, “I am doing this so that I can get to know you. If I do not know your name by the end of the course you are not going to get an A.”

During my days I prepared for the next class, read their papers and visited schools. When I read the papers, I looked at the photos and memorized faces. I got to know their voices, their concerns and saw their progress as individuals. By the next class I had read every paper and made comments on them. Some of my comments were nearly as long as their entries. I loved the conversations that ensued in writing as we talked and shared ideas. I didn’t give grades, but rather relied on my comments.

At the beginning of the course, writing was scant and awkward for some for the students. I was told that Jamaicans don’t write. I interpreted this to mean that Jamaicans don’t like to write so they avoid it if possible. However, as the two weeks went on the writing became more complex in both length and content. As I read their papers at night, I selected 5 or 6 and asked them to read part or all of their entries as a way of celebrating their writing, but also as a means of reviewing what we did the night before.

“Will you share this?” I wrote on their papers.

When they received the pages back the next day, they read my comments which were a direct response to what they had written. Five or six had a comment asking them to read their paper or part of it aloud. As they stood up to read the section I marked, the others listened and applauded. Over time it was evident that they gained courage and felt proud of their work.

I noticed that having them share their writing brought smiles and pleasure. The result was that they became more confident. Because of the beautiful example we found in Lucy Calkin’s work, their language became more expressive and colourful. I discovered that their voices matured into creative and critical expressions about the text or class. It was a wonderful way to review what we had talked about the previous day.

The War with Grandpa

Each night I took 10 – 15 minutes to read aloud two or three chapters of The War with Grandpa identified as a grade 4.5 reading level novel. It was a break from the challenging ideas being discussed, a breath of fresh air for all of us. Some nights I reluctantly put the book down in order to continue with our content. Some nights the students begged for more.

The War with Grandpa is an endearing story of growing up, dealing with being older and learning to compromise. Grandpa moves into the home and is given the boy’s bedroom. Thus begins and adventure of revolt, trickery and eventually compromise that leads to peace and joy. Chapters like ‘Only a Dope will Mope’, ‘Night Attack’ and ‘A Flag of Truce’ take the reader or in this case, listeners, along a humorous trail that reflects issues of youth and aging that transcend culture and environment. No one ever complained that the story didn’t take place in Jamaica. In the end the boy writes a story for his teacher. He concludes, “Anyway, this is the true and real story of Peter Stokes and the war with his grandpa. I hope you like it,” I think we all felt a little sad that the story was finally over.

Literature study groups

Another part of the class that the students particularly enjoyed was small group discussion. Each group selected part of the book to discuss. After about a half hour they brought their comments back to the whole group. Often this was in the form of a report, but eventually they began to get creative. They would dramatize or create something poetic to highlight an important point. As the class progressed the creativity of the students and their expression of culture dominated the learning. When students understand that learning connects to who they are through cultural relevancy, learning is solidified.

Last night of class

The last night of class was an evening of celebration. The story reading was finished, papers had been shared and now for one last time the groups met to form a conclusion of their study. After about 30 minutes of time to prepare, we would come together for music, drumming, laughter, dramatizations and more. I remember one occasion when the students had prepared a dramatization of a class that reflected a teaching strategy they felt was important. There was a teacher and students in the drama. The role-playing students were chattering away in the local patois. We all laughed. One of my students turned to me and said, “Dr. Headlam. We didn’t know you understood patois!” That made us laugh even harder. “Yeh mon, me can understan’ a lot more than onu migh’ tink.” My poor attempt was met with more laughter, but appreciation that I made the attempt.

At the very end of the class I was given praise and affirmation. Grades were also handed out to each member of the class. It was rare for anyone to get anything less than the A. I knew them well. I knew their voices, their experience and their reflections. Not only did they meet my expectations, in most cases they exceeded them.

When the final moment of class came, there was a quiet time. Students gathered together and brought me a present. My apartment in Ocho Rios is filled with wonderful paintings and one particular gold framed version of the Serenity Prayer, “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, Courage to change the things I can, And wisdom to know the difference.”

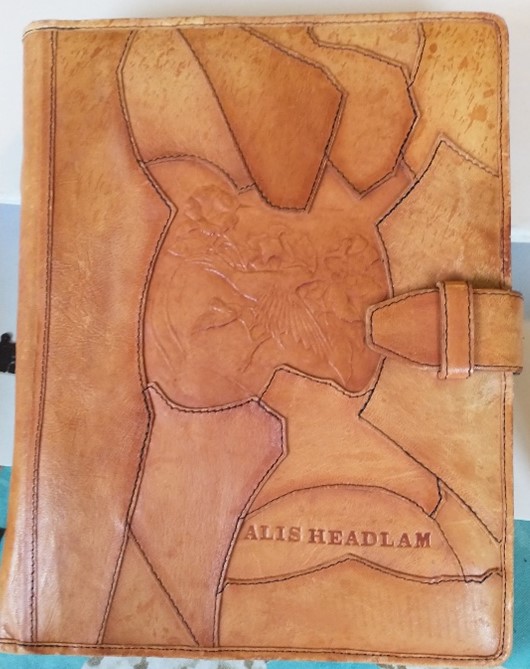

The most special gift however, was given to me after one of my first classes in Montego Bay. As I opened the brown wrapping paper, I uncovered a light brown leather notebook with my name and the national bird, the Swallowtail Humming Bird, engraved on its cover. For years now I carry this with me wherever I go and write my notes in it when I attend meetings. The warmth of the leather in my hands is an enduring reminder of the wonderful times we had together in those classes.