“Control your own mind, and you may never be controlled by the mind of another.” — Napoleon Hill

A few years ago, after experiencing great pain due to having read segments of African American history, I penned the following words in poetic form. They were intended to form a literary memorial not only to my pain, but also to a solemn moment of enlightenment. The poem was titled, Kulan, an African word, which in English means “meeting” or “encounter”. The piece speaks of a psychological and cultural amnesia which developed as a result of the tragic effects of European imperialism, colonialism, and chattel slavery which was foisted on people whose progeny now find themselves in the African diaspora:

Ah, my baby, I have found you!

I have looked long and hard, and have searched high and low!

Across many seas and in foreign lands

I enquired after you, weeping bitterly and loudly in the streets!

Ah, my child! My ingane! At last!

But, oh, my precious one! My kauna! What have they done to you?

Why do you not understand me?

Why do you look at me with mashaka and also with great scorn?

Embrace me and do not pull away!

I am your mama! Twas I who birthed you and I who suckled you!

Tis my blood flowing in your akwara!

Your gait is mine, as are the inflections in your voice.

The tunes you hum are not strange.

Omens, yes, but only to those who oppressed and derided you.

With them I rocked you to sleep in my arms.

With them I taught you how to till the soil and to care for family.

You learned to dance to the rhythmic beating of the djembe, and to the plucking of the strings of the kora.

The strength and dignity of your forebears were told, and retold through generations but in their own tongues.

This is your Day of Pentecost. Do you not hear Yoruba, Hausa, Zulu, Swahili, Igbo, Xhosa, Arabic and Shona?

And, no! Your name is not “Nigger!” You are, Gamba, for your hands were bred for both the spear and the shield.

Bayede! Bayede! Bayede! Inkosi yezwe! Ingonyama! Ophethe! Malik! Saka! Bayede! Bayede! Bayede!

Ingane, I have found you. It is now up to you to find me, to follow me, to learn from me and to be all you can be.

My kauna, I offer you a cup of water from the rivers of your people, but you and only you can and must drink of it.

And what is my name? How sad. How sad that you have to ask. I am your titi, isifuba, zamu, ara, webele – I’m Africa.

The spirit behind my humble attempt at poetry was one that was aroused from quite a few seminal works that were written by intellectuals of the African diaspora about the African American and the African Caribbean experiences, and by those non-Blacks who were, somehow, made free from the ubiquitous bias of white racism. White society has sought and it continues to seek to corrupt, to blot out, and in the most blatant manner, all of the historical achievements of people of colour. And, if that was not bad enough, when it did not seek to convince the Black man that slavery was good for him, it argued, ironically, that the slavery of Africans never ever took place.

Works such as Dr. Alain Lock’s, Voices Of The Harlem Renaissance; such as Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s, The Mis-Education Of The Negro; such as Franz Fanon’s, Black Skin, White Masks; and such as Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois’, The Souls of Black Folk were among those whichformed the fountainhead of the intellectual river of my own awakening. And as the attempt at erasing the history of the Black race from the whole consciousness of man continues today I have asked myself if it is really necessary to play this scurrilous and this sordid mind game with white society?

The history of medical science tells us that a lobotomy is a surgical division of nerve tracts in a lobe of the brain, which is used in the treatment of epilepsy and of (formerly) severe mental illness. The procedure was strongly linked to severe memory loss, as it damaged or it severed connections in areas of the brain which are essential for memory formation.

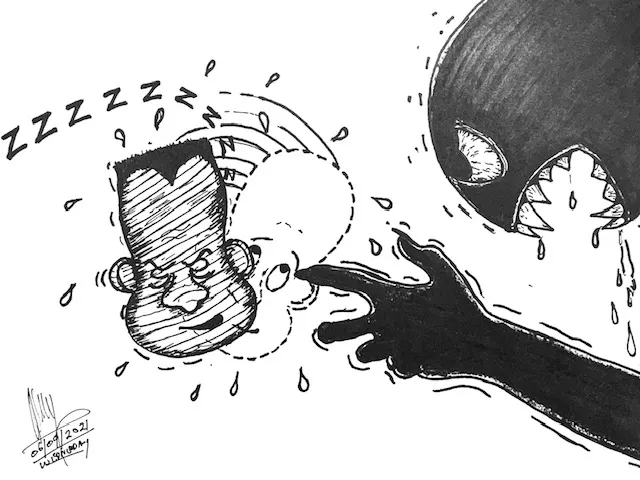

And so, although the scalpels used, medically, for lobotomies were different from the psychological and social tools used to hoodwink the Black man and to rob him of his past, the effect of the symptoms of amnesia in both are, without a doubt, strikingly similar. And yet, why should the Black man, especially within the African diaspora, not just accept his lot in life, not just let bygones be bygones and, simply, not just move on as best as possible? But, the answers to such questions cannot be adequately supplied without first providing answers to the following questions.

Why is the ontology of the Black man — that branch of study which examines the nature of being — tied to Western white society’s experiences with and its biases against him? Why should the Black man — whether living on the African continent or within the diaspora — allow himself to engage in any discussions with white society concerning himself, and with the usage of European constructs of what is considered to be culturally, ethnically and racially good, beautiful and bright? Why should he condescend to play the mind game?

Why should he engage in its old wives tales, especially if they are not based upon historical and anthropological facts, nor inspired by an honest and open-minded approach towards mutual understanding and respect, but, instead, upon preconceived ideas of racial superiority in tandem with an agenda of Black exploitation and oppression? Why should the Black man give the white man any of his time or his attention? Why should he, by his response, validate anything found within white society?

In the normal course of life we tend to disassociate ourselves from others who do not accord us any respect, and we also, completely, ignore those who cannot be trusted — thus preventing them from entering into our private and hallowed spheres of intimacy. So, why should the Black man feel compelled to associate with the white man, whether he be Anglo-European, Franco-European or otherwise?

The African American poet, Paul Laurence Dunbar, in his piece, We Wear the Mask, revealed one of the strategies that people of colour have been using for hundreds of years in order to survive in white society:

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Why should the world be over-wise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay, let them only see us, while

We wear the mask.

We smile, but, O great Christ, our cries

To thee from tortured souls arise.

We sing, but oh the clay is vile

Beneath our feet, and long the mile;

But let the world dream otherwise,

We wear the mask!

The black man was forced into this mind game by the white man, through hypocrisy and oft at the point of a sword, in order to feed the latter’s insatiable, intractable and implacable appetite for power and for domination over all races of people who do not look like him and behave like him, who could serve to fan the flames of his delusional ego of racial and cultural superiority, in the wake of him having robbed, him having raped, and him having pillaged all that the other races enjoyed before European imperialism, colonialism and the enslavement of Africans.

Why should the black man feel it is necessary to defend himself against all of the baseless and the denigrating assertions that have been levelled against him by the white man? What if the black man, simply, ignores him? Can the black man afford to do nothing in the ontological war that the white man has launched against him? History suggests that if the black man does not defend his self-esteem, then he would be liable to lose his dignity, completely, in the very same way that he did when the white man took away his land, took away his mineral resources, and took away the vigour of his forbears in order to enslave and to oppress them.

And so the vestiges of the black man’s extant history — untarnished by European hubris and by white racial bias — comprise his last stand. Knowledge of himself is a line drawn in the sand against total extinction and complete obscurity. It is where he and his people have mustered and have re-formed the line against the evils of European ethnocentricity and racial bigotry. It is where he and his people either “do or die”. And, should he and they survive the swelling tide of neo-colonialism and oppression they would stand a chance of getting a foothold — a beachhead even — towards reclaiming all or some of that which was so callously taken from them through trickery and violence, thus providing a basis for building something that is new and lasting for themselves and for their progeny.

The black man and his people never asked for this war. The black man and his people do not relish the idea of being embroiled in it any longer. But, in the face of unrelenting racism, which hounds and which harasses them, every day, what else can they do? Even if they wanted to walk away from the struggle in which they are now engaged — out of sheer resignation if not out of a sense of peace — they are constantly goaded into defending themselves because of the taunts, because of the petty slights, and because of the overt brutality of white society against them.

And so, the black man has no choice but to study, but to ponder, but to debate, but to write and to make his case before the wider court of world opinion. In closing, the following words from another attempt at poetry on my part, which I had named, For Good Measure, sought to convey the defiance and the resilience of the black man, one who has long been out of place in a world which was forced upon him, as if he were an elephant which was transported from the warm tropical grasslands of the south to live as a polar bear within the cold arctic snow of the north, and then to be observed and to be unfairly assessed by an alien culture:

Don’t you measure us with that broken yardstick.

Cut the plank from an African tree and then use it,

Not from a cold, a deciduous, or a strange one.

Take it from the base of Kilimanjaro and not the Alps,

From our forest, sun burnt, not frostbitten, carved.

A trunk from which our drums are made and played

Mahogany, Ebony, Limba, Bubinga, and Tamarind.

Branches tall, and commanding the respect of the mighty elephants,

Where the Black Panther lies in wait for prey

Where a troop of monkeys will chatter and then scamper.

The high perch of the eagle and the home of its nestlings,

Foliage teaching young giraffes to stretch and grow,

Leaves sprinkled with Saharan sand by the harmattan

Wet from tears of dew shed for those who were uprooted.

Grandeur upon which the expanse of the grasslands gazes.

Use any leafy bower which casts a long, friendly shadow.

As it sees its reflection in the Zambezi, let’s see ourselves,

But don’t hang your plumb-line from any of your trees

For depth and rectitude of soul can only be found with ours.

Speak to the woodland gently, and it will give what you need

Near communal fires where old men recite our traditions.

For it is then and only then that you will see us as we are.