What does the Christian Bible reveal about God’s attitude towards the institution of slavery? In the process of biblical interpretation, it is always the intent of sincere, competent exegetes to cognize the mind, the persona, and the will of God of the Christian Bible as He is said to have revealed them and had them recorded, rather than what mere men think that they ought to be.

To some degree, their approach is akin to that of Anthropology, the study of what makes us human. Anthropologists take a broad approach called ‘holism’, seeking to understand the many aspects of the human experience. Through Archaeology, they explore how human groups lived hundreds or thousands of years ago and what was important to them. Applied Anthropology is the application of the methods and of the theory of Anthropology to the analysis and the solution of practical problems.

Good biblical interpreters are also like those engaged in the field of Psychoanalysis where every effort is made to discern how people see themselves, and to appreciate definitive terms which they had ascribed to themselves and that were not created and foisted upon them from sources that are external and alien to them.

Christian theologians, and I am sure of those in other religions, seek to understand God’s thoughts through the commandments codified in Holy Writ, as well as through His interactions with mankind as they apply or misapply them.

From a Judaic-Christian perspective, our world is seen as having fallen outside of the perfect will of God. Consequently, sin becomes an overarching spiritual principle which permeates, influences and alters every human relationship away from the original, divine intent. Therefore, the Christian Bible, or any other religious sacred text for that matter, can only be understood contextually from what was revealed as God’s intent before the fall of mankind into sin, corruption and death; from what He prophetically envisioned for them in a new world after the one now being ravaged by sin; and from all that He did and that He continues to do for mankind within what Christian theologians call the probationary period — the nexus between limited time and limitless eternity.

Vices such as covetousness, theft, deceit, exploitation, violence, murder and war, for example, are diabolical symptoms of man’s choice against God and were, nonetheless, allowed to become part and parcel of their life experience. According to the Christian Bible, God placed two choices before Himself in response to that rebellion. He could have, sovereignly and rightly, destroyed mankind outright, without any opportunity for appeal to His divine mercy. However, He chose, instead, to work with man within such a world using, when appropriate, its broken reality towards redemption with a sin-free reality. The story of Jesus of Nazareth — the man and his mission — is seen as the exemplar, the driving force and as the culmination of that plan in Christianity. And so, with all that having been said, what does the Christian Bible reveal about God’s attitude towards the institution of slavery?

There is nothing in the Bible — neither in the Old nor New Testament — which singularly, which unambiguously, and which declaratively encourages or forbids the practice of slavery. (There, I said it). And yet, conversely, as God sought to work out His perfect plan towards redemption — from Genesis to Revelation — the issue was dealt with in both. Except for the violent overthrow of the slavery of the Hebrews who were in bondage to the Egyptians for 400 years, there is no prescription for physical rescue stipulated in the Christian Bible for those held in bondage in similar circumstances. In fact, while in the throes of a ministry of reconciliation, the Christian is made vulnerable to persecution, to ostracism, to privation, to oppression, and even to death.

Since this Egyptian-Hebrew affair, the reason behind this apparent proclivity of God’s people to willingly acquiesce to such evil in order to keep the peace and to win people to Christ has been the bane of Christian theologians for centuries. The writings of Moses and those of the apostle Paul have been central to the discourse on this thorny issue of slavery. Given how the Christian Bible presents the character of God, it is not unreasonable (though likely unwise) to interpret it as it saying that He tolerates slavery, even if He does not actively promote it.

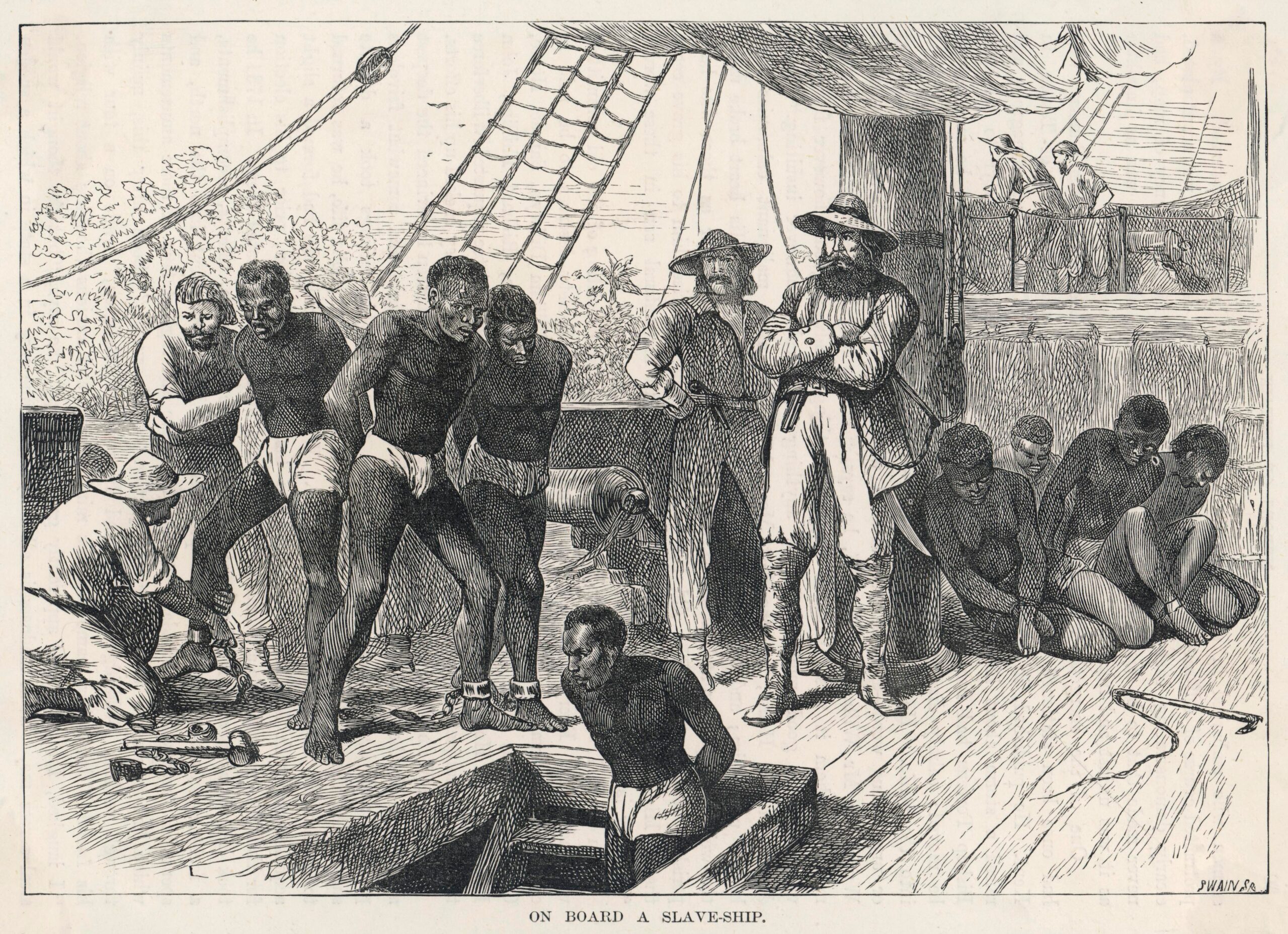

Even as a devout Christian, this writer wishes that the Bible articulated more definitively and aggressively against slavery as it has done so in regard to murder, covetousness and theft, for instance. Interestingly, all those vices are enshrined in the practice of slavery as recorded in world history, especially in chattel slavery as practiced by Europeans against people of African descent. The overt antipathy of and forthrightness by God seems to be reserved for the following statements made by Him through His prophets and his apostles:

“The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me; because the Lord hath anointed me to preach good tidings unto the meek; he hath sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to them that are bound; To proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord, and the day of vengeance of our God; to comfort all that mourn….” — Isaiah 61:1–2. And,

“Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature.” — Mark 16:15

And, “For all the law is fulfilled in one word, even in this; Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.”

— Galatians 5:14.

Now, let this writer hasten to remind you, his dear readers, that the concept of a neighbour within the New Testament biblical dialectic was inclusive of strangers and of those deemed to be one’s enemies. The parable of the Good Samaritan is but one example of the divine view on the issue of good neighbourliness. This conflicts with the white, racist theology on slavery.

No passage in the Christian Bible provides a predicate for the justification of slavery. In fact, too often scriptural interpretations are twisted into a woeful eisegesis, placing them under a pall of suspicion and judgement. Exegesis, on the other hand, is a legitimate interpretation which reads out of the text what the original authors meant to convey to their readers. Eisegesis, on the other hand, occurs when people read into the text what the interpreters wish to find or think that they have found therein. It expresses the reader’s own subjective ideas and not the meaning which is in the text. The latter was the case with the European kidnappers and enslavers of African human beings.

Slavery was no more a part of the plan of heaven than was polygamy. Yet, when God chose to engage mankind into schemes conceived with a view to restore them back to Himself, He “winked” at such vices or moral turpitudes when He encountered them, but only for a time.

The Christian Bible states that He put constructs in place which, in due time, would comprehensively address the multiplicity of social ills with positive and eternal outcomes. God met people where they were at, God dealt with people where they were at, but God never left people where they were at. Within a perceived short view of His outworking of things were always the underpinnings of His long view on things. His expectations were and are ever the same, but His methodology for helping people to meet them was and will never be the same. One only needs to recall His establishment of the Old Covenant with His people and the fulfilling of it in the New Covenant, as was prophesied in the first.

The concepts of “process” and of “progress” are hallmarks of the Christian Bible. During the period of African chattel slavery, the white establishment anchored justification of their behaviour, falsely, in Scripture, with all the unwholesome, arrogant and selfish intent typical of the Christian heretic that the apostles fought against in their writings. They were like patrons in a buffet restaurant — picking, choosing, and refusing Scripture passages, or twisting them out of context to support their depravity, their lack of humanity, and their unbridled greed.

Consider, for instance, that in their hypocrisy they never released their slaves, as was stipulated in the Old Testament, after a seven-year Jubilee period. They never released their slaves after they had maimed them. They had never submitted themselves to the prospect of capital punishment for having taken the lives of slaves. They had never treated their slaves as human beings. Those hypocritical prigs also flouted the clearly stated prohibitions on kidnapping, and God’s commandments against the illicit and distasteful sexual relations that they forced upon their slaves. They “evangelized” the slaves but would not allow them the privilege of enjoying holy matrimony. This allowed them to breed them and to sell them as cattle, and to treat them as paramours.

This writer, not being privy to the full counsel of God, greatly regrets that the Christian Bible does not forthrightly excoriate, to full measure, a practice that he and every human being with a modicum of decency and of humanity abhors and finds reprehensible. But, he can only trust, as he does now, that his God will deal with them in His time as He has promised. Although challenging, making the Bible say what it does not say in order to make it more appealing to non-Christian’s would, in turn, make this writer as guilty as those heretics who attempted to use Scripture in support of their crimes. Be that as it may, this writer is no Barabbas, and understands that this is “the way of the cross”, a part of all that he had signed up for.

Indeed, what you have read here reflects a conversation between this writer’s mind and soul. While not the first such that this writer has entertained, it is, however, one which he found grossly uncomfortable and decidedly ill-equipped to address. It is one that he was inclined to give a wide birth, especially as a Christian; one that poses difficulties for the practice of his religious faith; and one which is likely to engender incredible agony of heart while still in the process of trying to address it judiciously with others who do not share his views.

Even so, having been challenged by truth, and having been goaded by inner promptings for outward displays of honesty, he found it necessary to run the gauntlet undeterred, letting the proverbial chips fall where they may.

In some respects, it presents a naked vulnerability of being. It can open a Pandora’s box of criticism and skepticism, perhaps leading to a humiliation of himself and a denigration of his God and of his faith in God. He could also have insulted the intelligence of his readers. Perhaps he has, and if that has turned out to be the case, then, please understand, that was never his intention. On the contrary, in accordance with his mantra ‘Consider this…’, it is an open-hearted offering, sharing with you, his readers, the tempests of his ruminations. It was a risk that he felt compelled to take. He now closes with the words of Martin Luther, the great German theologian:

“Here I stand; I can do no other”