The South American fire season is entering its last stages, and it has been one for the records.

The fire season (or dry season) has seen the Amazon, starting in Brazil, reaching an inferno stage while the world cries crocodile tears and does half actions. This has been so for many reasons, mainly because it is not the first time, but also because companies and, by extension, countries long for the cheap meat and agricultural products which will be produced on the recently burned land.

These nations and companies also yearn for the rare minerals and wood which would become readily accessible if ‘excess’ forest were burnt away.

I say crocodile tears because this is the logical outcome of the path and half action we have been on because surprisingly, France, Canada and a few other big countries came out to condemn Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro for the fires and seem to be pressuring him to ensure that the record-breaking fire outbreak doesn’t happen again, while not addressing the underlying causes.

While it is nice to see powerful nations demanding that something be done about this environmental and global destruction, I feel that we in the global south and particularly small states and small island states should be wary of what is going on in Brazil as that could be the template for us. We should become more vocal to ensure that it is not we who suffer the consequences of global warming while paying for the comfort of the global north and rich people in general.

How exactly does the Brazilian fire relate to Jamaica and how have we reached the topic of the south paying for the comfort of the north some may ask. My answer is that it is very obvious what the links are if one takes the time to compare the situations.

The Amazon is one of three areas which make up the lungs of the earth, the others being the Indonesian rainforest and the African forest. If these are destroyed, then apart from whatever greenhouse gasses they release, we would have lost a lot of the sources for the most basic necessity for life — air.

The Amazon is also home to one of the largest rivers in the world — the Amazon river — and it, along with its many tributaries, provides water to much of the people of that region. The people of this region who rely on the water for the most part are the indigenous population who have been there centuries before European colonisation. If it were to be contaminated, or worse still exhausted (used up or blocked up), then there again would go the second thing which forms the bedrock of human existence, at least for the people in South America.

What is going on in the Amazon is partly due to the dry season. However, it is largely a result of deliberately poor boundary demarcation and surveillance for protected forest areas. These areas contain large swaths of jungle and are home to scores of indigenous tribes. Due to poor planning, surveillance and enforcement mining companies, ranchers and loggers – some as independent actors but all with the open approval of the state – have come in to clear the land while also polluting any and all water sources they can find. This land clearance has led to the perfect conditions for forest fires and once the fire season came, we were left with what we see now.

Compare this to the situation in our Cockpit Country and one begins to see the glaring similarities and end results we seem to be heading towards. Much like the Amazon rainforest, the boundaries for the Cockpit Country have for decades been vague and remain as such even with the boundary mooted by the Government.

Again, like the Amazon, the Cockpit Country is the lungs of Jamaica, soaking up much of our carbon gasses and giving us oxygen. In that same vein, the Cockpit Country provides most Jamaicans with water. Much like the Amazon the main individuals relying on the Cockpit Country are our own indigenous population — the Maroons — descendants of escaped African slaves and the Taino-Arawak survivors of the Spanish genocide.

Like the Amazon, the Cockpit Country is rich in mineral resources (bauxite and possibly gold) as well as wood which is much wanted.

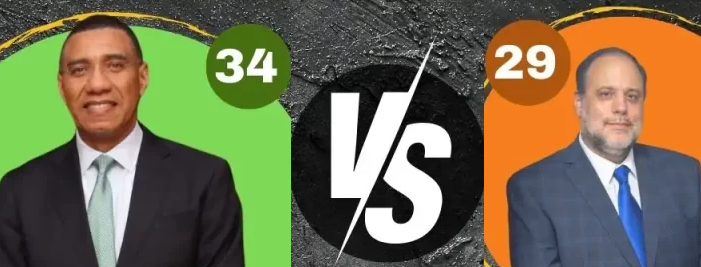

Now, I would never say that this is a like for like situation. We, for example, are not saddled with the pressures of a powerful cattle and mineral sector nor do we have the kind of leader at Vale Royal who acts with such disregard as Bolsonaro, but the parallels are still there and must be looked at before we go ahead and draw up a concrete boundary for the Cockpit Country.

We as an island, a small and poor one to boot, can ill afford to lose our main water supply and we certainly can’t afford to destroy our forests. It would do us well to look at the clean-up cost and the rehab cost for the Amazon and ask ourselves, can we even afford one-tenth of that if it came to us needing to fix any potential damage to our Cockpit Country?

Another thing that needs careful attention from both the state and the general public is the habit we have of progressing on the backs of the poor and weak. Climate change is no different in this manner, nor are the solutions.

In Mexico the largest windfarm is located smack in the middle of a slum which also houses some of the indigenous people. These people have borne all the burdens of this green tech, from the noise to loss of houses as well as illnesses. This Modus Operandi is not new, it should never be lost on us that the JPS stations are at Hunt’s Bay and Old Harbour and not Ocean Boulevard or the MoBay Hip Strip. It is the poor who pay for the advancement of society and it must be checked if we are to survive.

It must also be noted that even green technology requires mineral extraction so it is the global South that will, in the end, be dirtied in order to clean the world.

We see this playing out in insidious ways, for as the world weeps (rightly) over the Amazon, the big countries continue mining the hell out of Nigeria and Niger, ensuring that the forests and the waterways there become and remain unusable.

The big powers will be more than willing to save the Amazon at the expense of the Blue Mountain range, and we must guard against that. The thought may seem alien, but we seek to protect the Panda Bear and Mountain Gorilla while at the same time destroying their food source and habitat. This abuse is already happening and we the poor of the world must stand up. It is not enough to say ‘renewable energy’ it must be just and free from exploitation and not a redo of this current exploitative model.

At the end of the day we need to ask ourselves, as the protests in Honduras escalate — “based in large part against plans to privatize their waterworks and create a hydroelectric grid linking up central America” — what is a global good and how do we handle it? Do we, as the G7 suggests, buy it and exclude the local population from it or do we do as Bolsonaro has done and act as if national actions on their patrimony have no global impact? The choices made here will have long-term and species-defining ramifications and we must ensure that in the rush to ‘protect the earth’ we don’t condemn the poor to being the life-raft or sacrificial lambs on the way to a climate solution (or a more bearable world in the new climate reality as increasingly seems to be the case).

It is not enough to say ‘don’t burn the Amazon’ while eye the Cockpit Country and lands in Guyana (which border or are in the Amazon, depending on which boundary is used). We must ensure that the call is extended to include the small island states and the global south. It is we after all who have suffered the most as a result of industrialisation. It is we who will (and are) feeling the first wave and the most deadly waves of climate change. It can’t be us who pay both in terms of blood and treasure (carbon taxes, carbon credits and the use of our resources) to ensure that the persons who got us here live comfortably.