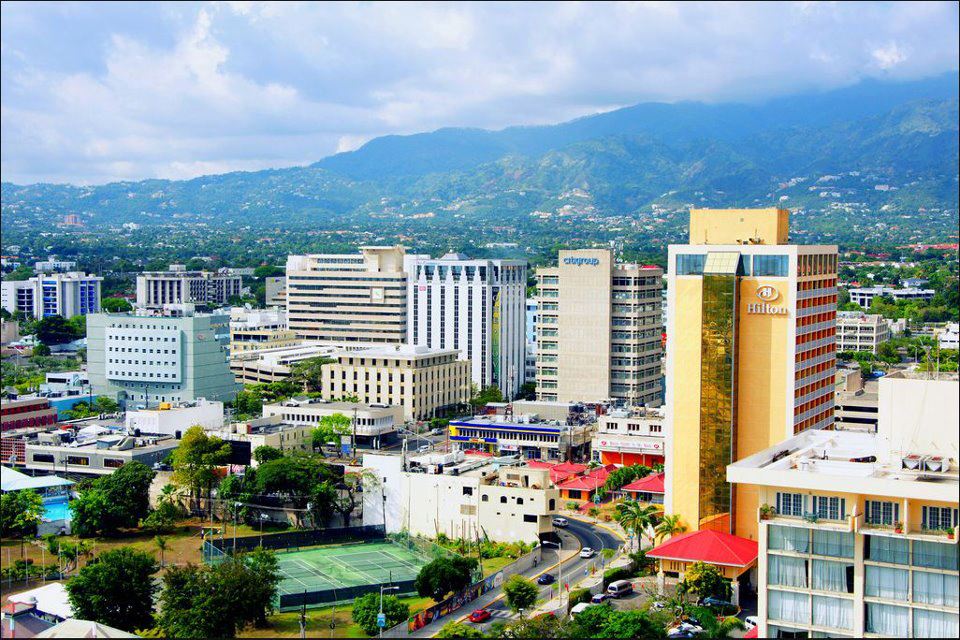

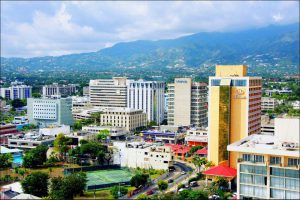

How is Kingston to be renewed and revitalized? Most times, responses to this perennial question focus on block and steel renovations and highlight the role the State and large corporations must play in initiating the revitalization process.

How is Kingston to be renewed and revitalized? Most times, responses to this perennial question focus on block and steel renovations and highlight the role the State and large corporations must play in initiating the revitalization process.

Over the years, grand announcements have been made and plans unveiled, but always they envision physical change, initiated primarily by these powerful players, preceding and driving wider social change. To the extent that change has occurred at all, it has been in fits and starts and with little input or buy-in from the city’s residents. While not denying the importance of improving the built environment and the role governments and corporations must play, this series has approached the question of renewal from a different perspective.

I have sought to encourage reflection on the cultural ethos of the city and how its character is shaped by the everyday actions and practices of ordinary citizens, on how our actions can contribute to a spirit of buoyancy, on one hand, or to fragmentation and a sense of despair, on the other.

Beginning in the 1950s, aided by incentives provided by the State, private developers and their clients embraced a model of urban growth based on low-density suburban sprawl. Rather than investing in the creation of more concentrated, mixed-income and mixed-use developments, the more economically stable middle and upper classes abandoned in large numbers, and in the name of progress, entire neighbourhoods of central and east Kingston within a mile or two of the city centre, for more distant residential suburbs. So these days, while sections of the market district remain bustling into the evening hours and on weekends, largely from the patronage of poor and working class people who live nearby and those who travel to and from Kingston by bus; much of the adjacent downtown business district becomes a ghost town after six o’clock, and even the majestic old churches in the area struggle to remain viable.

Walking or cycling to work or school, for shopping or entertainment is now disdained by most well-off Kingston residents and by many less prosperous ones as well. Habits that were commonplace up until the 1940s and early 1950s have become unthinkable for many. Yet it is still possible to resume, even if partially, these old habits, and the benefits of doing so are perhaps more tangible than ever.

Consider the costs we now pay for our sedentary lifestyles. The Jamaica Health and Lifestyle Survey pointed to the worrisome fact that the number of Jamaicans who reported they were physically inactive almost doubled between 2000 and 2008 and those reporting high levels of physical activity fell by 14% in the same period. These changes, the survey pointed out, correlated significantly with an increase of more than 5% in the level of obesity, as well as with increasing rates of depression, hypertension, and other risk factors.

Another way of illustrating the costs that those of us who insist on traveling by car now pay for this indulgence is to calculate the amount of fuel we waste simply sitting in traffic, never mind other vehicle-related costs. On an average afternoon during rush hour, for example, it takes around 45 minutes for a car to travel the 1.5km along Trafalgar Road between Lady Musgrave and Hope roads. Depending on the fuel efficiency of the vehicle, this might mean that the motorist is burning, each afternoon, between $400 and $700 in fuel just for that very short portion of their commute.

By comparison, they could have paid $100 as a regular passenger, or $40 if over 65, traveling all the way home in a comfortably air conditioned JUTC bus. And if there were dedicated bus lanes and fewer cars on the roads the buses would be able to travel their routes much faster and there would be no need for the expensive road-widening schemes we see taking place in Barbican, Constant Spring, and elsewhere.

Even as the creation of more and more distant suburbs continues apace in Kingston, and dependence on private cars increases, this model of urban growth has come ever more sharply into question internationally. Jamaican-born professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Connecticut, Norman Garrick, a leading urban planning and transportation expert, is among those who have been rethinking radically the policies that have led to sprawl and the favouring of private automobile transportation in North America and elsewhere in the world.

Garrick’s studies show that cities such as Cambridge, Massachusetts and Portland, Oregon, that have worked to maintain lower automobile densities, paradoxically enjoy higher rates of job creation and urban residence and greater urban vitality than cities that have engaged in “auto-first” planning which prioritizes the expansion of highway access from the suburbs and creation of more and more parking facilities in the city centre. Parking lots and garages, Garrick points out, are a relatively unproductive use of urban space and other resources that could be far more productively used for housing and for commercial and cultural purposes.

Several of our own leading architects and planners, like Clifton Yap and Ann Hodges, have also advocated that we shift our urban planning strategies and priorities in Jamaica: recommending that we more closely integrate our urban design and transportation planning; that we prioritize mass transit over private automobile travel, and shift to more mixed-income, mixed-use, higher-density urban development.

In light of some of the special pleasures of Kingston living that I have described in earlier articles in this series, we might also want to think systematically going forward about those sites and those moments, the spatial locations and temporal events, such as well-maintained parks and public spaces full of interesting programming, that serve to bring residents of Kingston together. How might we increase the density and richness of such sites and moments?

Stepping back from planning strategies that favour the automobile requires that we create first-rate public transit. As I have argued in earlier articles, walking and using public transportation can allow for a new appreciation of Kingston’s hidden gems and physical attractiveness. More importantly, walking the city fosters democratic values and connects us with others in ways that serve to build understanding and community.

In a riveting TED Talk titled ‘Why Buses Represent Democracy in Action’ given in 2013 that readers can access online, the former Mayor of Bogotá, Colombia, Enrique Peñalosa, proposes that “an advanced city is not one where even the poor use cars, but rather one where even the rich use public transport”. Following the democratic principle of equality under the law, he points out that a bus carrying 80 passengers should be entitled to 80 times the land space a private car transporting one person occupies.

Building on such examples and on his successes, as Mayor of Bogotá, to make the city more pedestrian-centred and develop a mass transit bus system, Peñalosa makes a powerful case for all countries, including poor ones, to invest scarce resources in mass transit systems, dedicated bus and bicycle lanes, and pedestrian green-ways as important means of promoting equity, enhancing quality of life, and expressing fundamental democratic principles.

Discussions about the renewal of Kingston commonly focus on the building and remodelling of physical structures and on what politicians, municipal authorities, the State, and private businesses need to do to revitalize the city. Obviously, attending to the built environment is important, and these players are critical. However, we as private citizens need not wait on the State, city authorities or businesses to get the ball rolling. As I have suggested in this series, fostering new ways of relating to the city; embracing again habits of walking and of face to face interaction; deliberately and routinely seeking to engage each other across the boundaries of the politically and class divided turf we’ve created; replanting shade trees along roadways and boundary lines to bring renewed softness and beauty to the city and to make walking a more pleasant and comfortable experience are all actions that we can initiate on our own and that can enhance, both individually and collectively, our quality of life.

These things neither require the intervention of nor funding from the State, nor do they require the approval of politicians. They are simple things that can enrich our lives together and, once they take hold, can serve to create a social climate in which the State might then be forced to shift its priorities and lend its support.

I do believe though, Mr. Moss – Solomon, that the delivery of the subject matter in our current education system is where the radical change is needed. To capture the interest from a majority of current students as well as to survive (not even thrive) in the current global space practical experience needs to be alongside or even before the theory. Example, use of a screw driver of different lengths to unscrew and finding out a longer screw driver requires less personal effort. Following up with the theory that work = Force x distance, where if distance is increased, less force is required to do the same work would quickly come alive.