Together, we are groping our way through a time of unprecedented anxiety, distress, and uncertainty. Anxiety in the face of a potentially deadly disease that so far has no antidote. Distress at the suffering it has provoked all round. Uncertainty as to what will follow: when and in what form our children’s education will resume; whether the peace will hold, or social anarchy ensue; whether our means of livelihood will return; whether the world we knew is now permanently in jeopardy.

One precious opportunity that this time of pandemic has gifted to us, however, is a moment for reflection. By abruptly suspending the normal it affords rare opportunity to reflect on that normal and change it in fundamental, positive ways. As Arundhati Roy writes in an essay in the Financial Times that’s been read around the world, “The Pandemic is a Portal,” this moment “offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves. Nothing could be worse than a return to normality.”

Interconnectedness

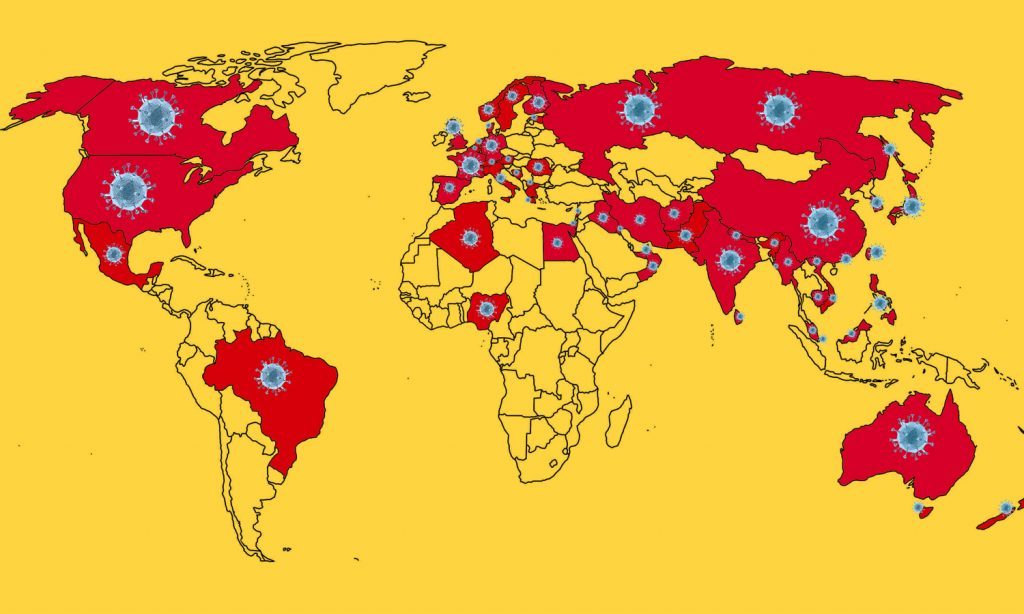

Even as we experience this moment in intensely local ways, confined or closely tethered to home, we are acutely aware that it is a global moment and that we share its confinements and anxieties with people all over the world. While we experience uniquely and up close the joys, tensions, and limitations of our own circumstances as individuals, families, and small communities; we are aware at the same time that people across the world are facing similar joys and challenges, though in different ways.

Moreover, it is not simply happenstance that we share this momentous experience with everyone else on the planet. We are inescapably, inextricably connected to our fellow travellers worldwide. Like it or not, we are tied to each other. Indeed, it is our interconnectedness that has quite suddenly plunged us into this surreal new way of life. And just as surely, this frightening global crisis demands from us a collective, coordinated, and unified response.

The pandemic, then, forces us to recognize our shared planetary belonging or identity, our global citizenship. It also reinforces and deepens that sense of shared identity. Other experiences, like being passionately glued to the World Cup or the Olympic Games every four years — experiences that we share periodically with billions of people around the world — also imprint on our imagination a sense of planetary interconnectedness and shared belonging. This COVID-19 moment, however, is more immediate and all-pervasive: everyone is experiencing it at the same time and in a visceral, bodily way.

Indeed, this is how all collective identities are forged over time: through the ceremonials of repetition, and undergoing memorable, shared experiences. Christians coming to know themselves as “Christians,” in part, through the weekly communion and the annual ritual celebrations of the birth and death of Christ, shared with fellow believers all over the world who they will never meet face to face. Muslims coming to know themselves as “Muslims” through shared worldwide observances like Ramadan. People of whatever nation state coming to know themselves as having a collective “national” identity through participation in the shared ceremonials of the primary school system, national holidays, and other collective experiences.

Religious, ethnic, and national communities also come to achieve their identities in common through painful experiences of persecution and hardship, the horrors of war, and other calamities. So far, however, our world identity is not institutionalized; we have no global ethic capable of regulating our lives together; we lack the ability to visualize and name our oneness. Without these it remains vacuous and trivial.

Contradictions

This time of pandemic is one of ambiguity and massive contradiction. It reveals both our enhanced global capacity for the early detection and rapid international communication of health threats like COVID-19 as well as the capacity for mobilizing scientific research and mounting a response. However, it also reveals the inadequacies of our present systems: the insufficiency of research and healthcare facilities across the global south; the fact that vital international organizations like the World Health Organization are seriously under-resourced and susceptible to political and fiscal pressure from member nation states; and more. The pandemic lays bare the inequalities and injustices at the heart of our social order: that poor and marginalized people are yet again the most vulnerable to infection, and the least equipped to take precautionary protective measures or provide sustenance for their families in times of crisis.

We have seen countless inspiring examples all over the world of neighbourly acts of caring; people arising to serve, support, and uplift others through music and the arts; voluntarily providing labour and supplies to frontline workers and the vulnerable; and others. Yet we are also painfully aware of the many instances of ethnic and national stereotyping: recrimination and blame heaped on Muslims in India, peoples of Asian background in the United States, and immigrant, poor, and minority populations in various parts of the world.

Discrimination and scapegoating have assumed new forms as groups like the elderly, nurses, and other healthcare workers are shunned out of fear or cast aside out of callous indifference. New forms of Othering have surfaced to create distinctions between “Us” and “Them.” At the same time, the futility of such discriminatory tendencies is now equally evident: the boundaries of Otherness rapidly shift; in a split second they may be redrawn to include those who are now doing the shunning. These boundaries are neither tightly sealed nor do they offer lasting protection.

The pandemic has made more acute our perceptions of basic human rights and their absence. In the face of the glaring inequalities we see across the world, COVID-19 brings more urgently to the fore the right to adequate healthcare, education, and shelter. If people do not have access to basic amenities such as clean, reliable water supplies and soap, they cannot fulfill the vital actions being asked of them by the authorities. Even as we more readily perceive our interconnectedness, we are aware that present international systems fall far short of meeting the needs of a unified planet. Yet we also recognize that people, conscious of their newfound oneness, can change these systems to better serve everyone’s needs.

Community

Our present crisis, then, highlights at a global scale, the interdependence between individual and collective, Local and Global, Us and Them. But it also reveals the impediments that prevent us from being able to respond in unified and effective ways. It shows us too that human beings are not inherently selfish. While strategies for controlling COVID-19 have required physical distancing and quarantine, we see people determinedly and spontaneously finding ways to interact and bring joy to one another. This moment of necessary stillness has made us a tiny bit less self-centered and nudged us towards greater awareness of and concern for community.

In an essay in The Guardian titled “The horror films got it wrong: This virus has turned us into caring neighbours,” George Monbiot contrasts the community self-mobilizations that have sprouted in the last few months with that “normal” which has locked people all over the world in its grip for the past four decades and more.

“You can watch neoliberalism collapsing in real time,” Monbiot notes. “Governments whose mission was to shrink the State, to cut taxes and borrowing and dismantle public services, are discovering that the market forces they fetishized cannot defend us from this crisis.”

As economic activity slowed and more people stayed home, the drive toward endless material acquisition has been dulled and it is now possible to contemplate with some detachment the idea that personal happiness ultimately comes from ever-greater accumulation. We can now more clearly see how striving to become multi-millionaires and giving free reign to our competitive instincts, erodes the social and deeply undermines community.

Monbiot comments further:

“You can tell a lot about a society from its quirks of language. We repeatedly misuse the word ‘social’. We talk about social distancing when we mean physical distancing. We talk about social security and the social safety net when we mean economic security and the economic safety net. While economic security comes (or should come) from government, social security arises from community” (emphasis added).

He cautions, however, that we still need the State:

“…to provide healthcare, education and an economic safety net, to distribute wealth between communities, to prevent any private interest from becoming too powerful, and to defend us from threats. It currently performs these functions poorly by design. But if we rely on the State alone, we find ourselves sorted into silos of provisioning and highly vulnerable to cuts. Rich social lives are replaced with cold, transactional relations. Community, then, is not a substitute for the State, but an essential complement.” (emphasis added).

Alas, as we have seen, while community has sprung up everywhere, it remains fragile and prone to fracture.

We must remember though that we have agency. Here’s Arundhati Roy again:

“Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

On the other side of COVID-19, can we imagine human beings as spiritual beings, and so begin to break down the mythologies of “Us” / “Them?” Can we transform our interconnected world into a unified world? Can we deepen the emergent spirit of community, and foster communities based on equity and justice that work in harmony with individuals and institutions?

These now confront humanity as urgent, inescapable tasks. The great luminary, Bahá’u’lláh, founder of the Bahá’í Faith, writing in the 19th century, anticipated these needs and sought to provide an overarching vision and the conceptual tools to cultivate changes we can now more clearly perceive as vital to humanity’s future.

“The earth is but one country and mankind its citizens.”

“Ye are the fruits of one tree and the leaves of one branch.”

“The well-being of mankind, its peace and security, are unattainable unless and until its unity is firmly established.”

“No light can compare with the light of justice. The establishment of order in the world and the tranquility of nations depend upon it.”

Through bold assertions such as these, and the guidance offered in more than a hundred volumes, Baha’u’lláh established the framework of a global ethic and laid a foundation on which humanity might embrace its oneness and harmonize its differences. Now might be a time to consider the guidance he offered.