There has been much talk in the news lately about the threat posed to established or recognized democracies around the world. The nemeses of democratic principles and practices have often been cited as “right wing”, “oligarchic”, and “totalitarian” ideological forces. Such nations as Russia, China, North Korea, Turkey, Syria, and Iran have often been identified as the leaders in this trend, falling into one or more of the above categories which vehemently oppose democracy, even to the point of being involved in state-sponsored terrorism around the world to achieve its utter demise.

All that being said, I began to wonder if this worldwide trend was due mainly to the idea that the masses, generally speaking, like to be ruled by the power exercised by political “strong men” — oligarchs and autocrats — over and against that of the power wielded by the masses themselves through the casting of votes at the ballot box?

Is such a penchant of the populace to be ruled by autocrats — whether such leaders are seen as benevolent or diabolical — due to their biological, psychological, spiritual, or cultural DNA? Is government of the people, by the people, and for the people, to paraphrase the American President, Abraham Lincoln, an anomalous social phenomenon, or a passing fad that manifests traits tending towards its own destruction — from its inception? How rational or healthy is the outworking of an ideology or a system which allows its citizens to speak derisively and rebelliously against freedoms that are recognized as human rights, universally?

What of the beliefs and practices which they can use to freely choose countervailing ones that could undermine, nullify or destroy the first? What then, are the limits of democracy?

The best of ideas and systems, even if conceived of on Mount Olympus, must be promulgated, administered, and defended on earth by individuals who stoutly embrace them. Such individuals also must possess not only the desire and the ability to execute such values, but they must have a burning desire to sacrifice their personal agendas for larger ones than their own — for “the greater good”. But do such individuals exist?

The concept of the philosopher king was first proposed by Plato in his dialogue, the Republic. It refers to a theoretical ruler who combines philosophical knowledge and temperament with political skill and power. The assumption was that such rulers would know what was best — better than most — from careful study and reflection, or through sage experience. But what does the evidence tell us from the experience of world history about philosopher kings, or of the plebeians who strive for such ideals? Some tyrants did have a blueprint for how to rule. Such individuals as Vladimir Lenin of Russia, Mao Tse Zung of China, Adolf Hitler of Germany, and Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore are cases in point.

It appears easier for tyrants, oligarchs and demagogues who exhibit a strong influence on their people, and who possess vast resources to foist their agendas upon the will of the masses, than it is for leaders who operate within liberal democracies who seek to lead by selfless altruism. The latter must depend upon the masses to cooperate with their agendas through persuasion, hoping that their electorates appreciate their versions of what is best for all, and that the populace will always be on their best behaviour even in times of dire need and fearsome crises. After distilling the various iterations of liberal democracy into, not only, such a basic democratic ideal as “majority rule” and, also, into the biblical axiom of “love they neighbour as thyself” is it, then, nothing more than a pipe dream — a quixotic utopian ideal — given that mankind is inordinately given to vice?

Some might argue that establishing more effective laws in most societies is not what is really at issue, but that the problem lies with those who are expected to obey them and also to enforce them. Some might argue that creating more resources is also not really at issue, but the absence of an egalitarian will in the disposition of resources. Is not that the case in Jamaica, and is not that the case elsewhere in the world? Is not that the reason behind the disillusionment of many in the various societies of the liberal democracies of the world with the electoral process, especially among those who feel that they are routinely disenfranchised, and who are often ignored in so many ways by the elite? Is that why people seem willing of late to throw caution to the wind, and to place their safety and that of their kin upon the altar of risk by defaulting to their baser, anti-democratic predispositions?

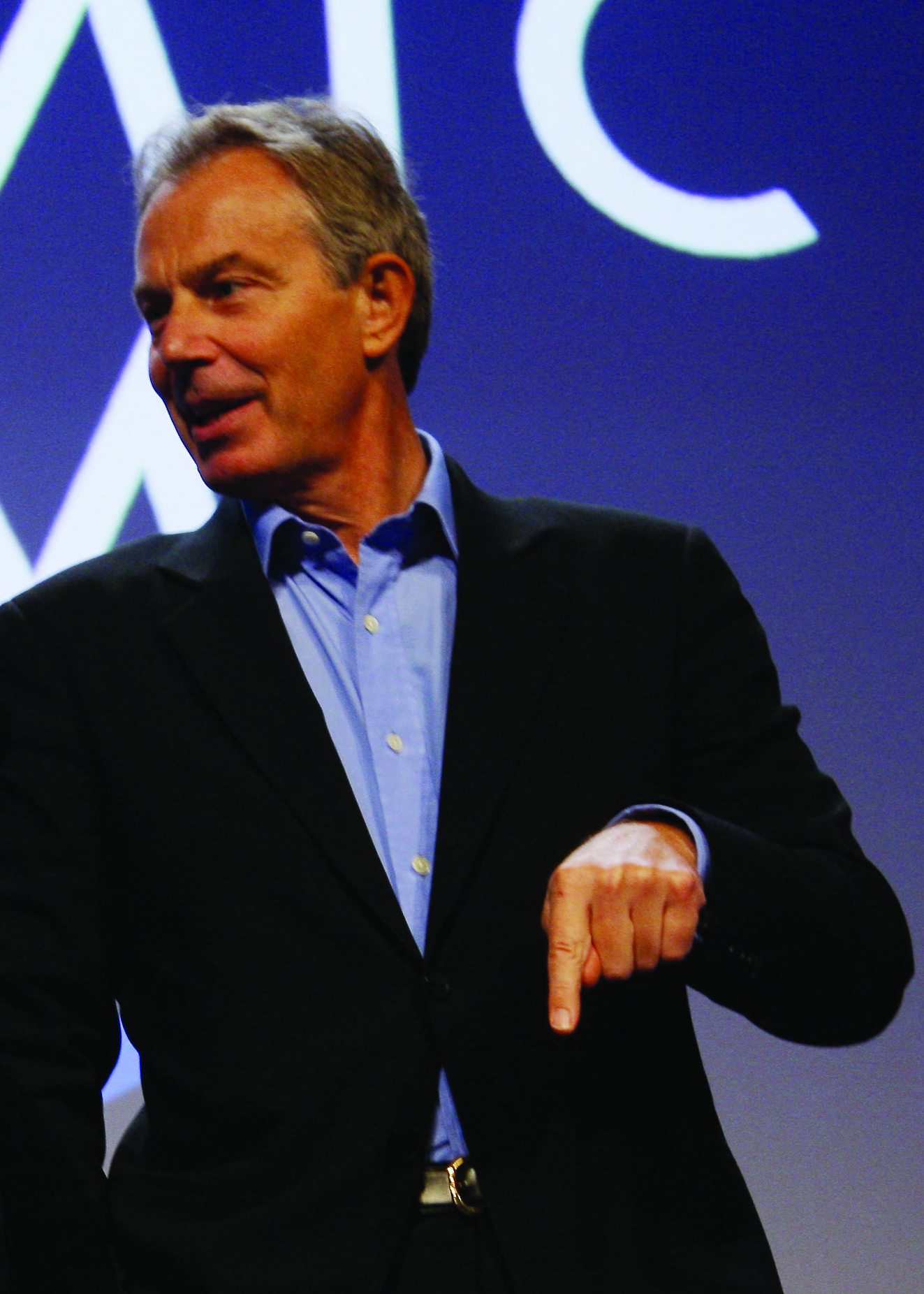

Mr. Tony Blair, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, expressed similar concerns about the state of liberal democracy in the world. In an article in The New York Times in December 2014, he penned the following words:

“Democracy is not in good shape. Many systems seem dysfunctional: The U.S. Congress, the coalition government in the U.K., and many governments in Europe have had difficulty making the decisions necessary to finding a way back to economic growth. Some fledgling democracies seem, in the short term at least, less competent to serve the needs of their citizens than some autocracies are.

Take all this together and add the profound nature of the challenges of recent times — the extremism convulsing whole nations in the Middle East and beyond; the ongoing financial crisis in Europe; the conflict in eastern Ukraine and Russia’s annexation of Crimea — and it is not surprising that we have seen the rise of far-right parties in Europe and a general sense of malaise and disillusionment with democratic politics. Suddenly to some, Putinism — the cult of the strong leader who goes in the direction he pleases, seemingly contemptuous of opposition — has its appeal.

We have become complacent about democracy. It remains the system of choice. It remains what free people freely choose. But it has what I would call an “efficacy” challenge: Its values are right, but it is too often failing to deliver. In a world of change, where countries, communities and corporations must constantly adapt to keep up, democracy seems slow, bureaucratic and weak. In this sense it is failing its citizens. Why has this happened and what should we do about it?

We have forgotten that theories are only as good as they work in practice. So the technical nuts and bolts of democratic systems matter. The basic principle that the people should elect their government remains popular and obviously right, but its implementation seems to have gone awry. It is time to debate how to improve democracy, how to modernize it.”

Is modernizing democracy enough? Does it have it within itself to “modernize” itself, with the implication for a better system as Mr. Blair asserts? Or has it, despite the best of intentions, become so weak and so emaciated that it can no longer act in that regard? With the rise of anti-democratic forces in the world one might be inclined to believe that liberal democracy has reached its nadir — that it is now on life support, just waiting for someone to declare it brain dead and then, out of mercy, to pull the plug. But, it has shown itself to be resilient, time and time again, even when the forces amassed against it were formidable and intractable.

Who would have thought, for example, that in its nascent days of modernity that it would have toppled and incorporated kingdoms? Who would have thought that it would ever have seen the light of day again after Hitler’s rule in Germany? Who would have imagined it triumphant against racist Apartheid in South Africa? Who would have anticipated victorious battles of the people against President Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and against President Trump in the U.S.? What of our violent political struggles in Jamaica? And yet, despite its fragility, it is still hanging on, if by nothing more, than a piece of thread. And, what does it say of the power of the nobler side of men against their baser, more destructive side?

The Economist Democracy Index, published by the Economist Group, is an index measuring the quality of democracy across the world. The index, a survey done on 167 countries, is based on 60 indicators grouped into five categories, measuring pluralism, civil liberties, and political culture. In addition to a numeric score and a ranking, the index categorizes each country into one of four regime types: full democracies, flawed democracies, hybrid democracies and authoritarian regimes. Of the 167 countries 8.0% are full-democracies, 37.3% are flawed-democracies, 17.9% are hybrid regimes, and 36.9% are authoritarian in nature. Such countries, for example, like Jamaica, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, the United States, Belgium, Cyprus, Greece, and Italy are seen as flawed democracies. In such nations elections tend to be fair and free, and basic civil liberties are honoured. But they may have issues (e.g. media freedom infringement and minor suppression of political opposition and critics). These nations can have significant faults in other democratic aspects, including underdeveloped political culture, low levels of participation in politics, and issues in the functioning of governance.

Hybrid regimes are nations with regular election frauds, preventing them from being fair and free democracies. These nations commonly have governments that apply pressure on political opposition, non-independent judiciaries, widespread corruption, harassment and pressure placed on the media, anaemic rule of law, and more pronounced faults than flawed democracies in the realms of underdeveloped political culture, low levels of participation in politics, and issues in the functioning of governance.

I leave the readers, in the interest of space, to extrapolate from those two categories what is entailed in full-democracies like Barbados, Canada, Austria, Denmark, Finland, France and Germany for examples, and in authoritarian regimes like Russia, Cuba, Nicaragua, China, Myanmar and North Korea for example. The index compiled on the same theme by the Julius Maximilians – Universitat

Wurzburg showed comparable results to the Economist using such descriptive terms as “working democracy”, “deficient democracy”, “hybrid regime”, “moderate autocracy”, and “hard autocracy”.

What is clear from those democracy indexes is that the nobler aspects of mankind have not and are not showing signs of rolling over and playing dead to their baser sides, despite data that show them to be greatly outnumbered. Although democracies around the world are faced with existential threats from without and from within there are forces that have been putting up resistance, with varying degrees of success. As the following Jamaican proverb asserts, so is the case with liberal democracy:

“Man nuh dead, nuh call him duppy”

— meaning that with the right support, anyone can rise against the odds.