There is understandable scepticism as to whether the wave of protests, following on the murder of George Floyd, will provide any lasting and sustained justice for blacks in the United States.

The Economist references how the unrest has “globalized the struggle against racism”; and I might add, how it must now focus our thoughts to the moral cause entwined in the struggle for reparative justice for all those who have been the victims of heinous crimes against humanity.

For people of African descent, this goes back to slavery — what is tragically the greatest evil ever perpetrated against humankind since the dawn of civilization. It ought not, and should not be allowed to be swept away by history without redemptive justice. Well beyond the physical enforcement of our labour — as despicable an act as it was — was the denial of our human existentiality and the psychological legacy of our own inferiority.

It is the legacy effects of that post-traumatic slave syndrome which raised doubt as to whether the nature and character of the protests over the last two weeks are pivoted around a common understanding of the circumstances of our history. The tragic murder of Emmett Till in 1955 brought to the fore the brutality of Jim Crow segregation in the south of the United States, and served as an impetus of the Civil Rights Movement. George Floyd’s murder 65 years after, is a graphic reminder that we are still a long way off from living out the universal creed that we are all one people bound in a common cause of humanity.

With the exception of JF Kennedy, almost all the US presidents before him never accepted the reality of racial equality. Even those who fought for the end of slavery also wanted blacks to be repatriated so they would be, in Thomas Jefferson’s words, “beyond the reach of mixture”.

Where the struggle for redemptive justice and racial equality is weakest is in our collective failure to re-educate blacks about their history and worth as a race. While we admit that slavery has defiled our human sensibilities and scarred our humanity, we seem prepared to accept the ‘white man’s teachings’ as the justification for our ‘right’ to protest violently — to loot, destroy and resort to violence — because we have been victimized, segregated, starved, brutalized and confined to a system of hopelessness and despair. Harvard University’s professor of African-American Studies, Cornel West puts it quite poignantly when he said: “I love my [black] brothers and sisters in the streets even when they’re doing wrong… But I love them enough to correct them.”

Marcus Garvey’s eternal crusade, rooted in throwing off the shackles of mental slavery, was popularized in song by Robert Nesta Marley as a final act of ‘baptism’ to bring about a new faith and restore a sense of pride, dignity and respect to ourselves. That seems to be woefully missing in some of the narrative embodying the protests over George Floyd’s murder, where ‘black lives matter’ seem only to be confined to state repression and institutional racism.

A recent article in the Miami Herald exposed that dichotomy in response to ‘black on black’ violence, and leaves the impression that we should not focus on that simply because black people who commit crimes are always prosecuted, while white police officers invariably walk free. A second argument — which could only mean that we are to overlook the significance of ‘black on black’ crimes — is that while 90 per cent of black murder victims are killed by black assailants, 83 per cent of white victims are killed by white assailants.

The late Professor Rex Nettleford, in his usual Nettlefordian style, exhorted us to an appreciation of the importance of the struggle for blacks to ‘be liberated from the obscurities of themselves’. And the late Professor Fred Hickling, in one of his last public appearances, spoke about the road to reparation being trotted by a people liberated through a process of social re-engineering.

We cannot overthrow the system through acts of wanton violence and destruction. That simply is not how it works. Perhaps, just perhaps, if we had come to the defence of Colin Kaepernick by boycotting NFL games and the players standing firm with him, George Floyd would have been alive today.

As a race, we provide little support for our own cause. The number of black banks fell 54 per cent between 2001 and 2016. There are now some 24 black banks still operating across the United States, and while the problem is much more than simply moving deposits, the challenge of overcoming the regulatory tightrope must be strategically faced, or we are simply doomed to a life as second class citizens.

The fact that the alt-right fascist groups and the antifa movement may be stoking the violence and looting does not excuse or justify blacks’ indulgence in such a practice. Like on previous occasions of protest actions against black killings, this must not be a moment but a movement, and we must look for the best of our past in this moment to mobilise for the new circumstances. We must define the essence of the struggle, even as the face and character of the demonstrations further reflect a response to President Trump’s assault on America’s First Amendment rights.

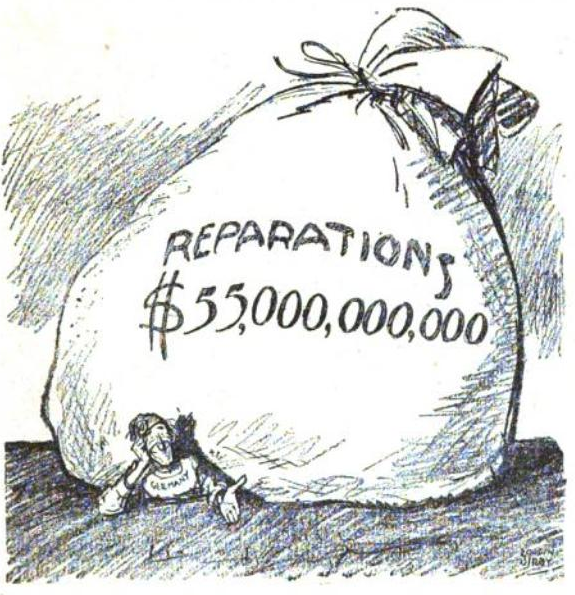

To walk the road from emancipation to reparation has to be embodied in the ideals of a global democracy. The American philosopher John Dewey said “Democracy has to be born anew every generation and education is its midwife.” People of African descent have a purpose of ensuring that democracy is defined in terms of equality and social justice through redemptive struggle, and the re-education of the black masses seen as its midwife.