When I was a boy, I wanted to be so many things, I wanted to own so many things, I wanted to do so many things, and I also wanted to go to so many different places. But, like countless numbers of children, the world over, I was not able to get all that I wanted, especially with the kind of parents that I had. And, when I was fortunate to have my way, their influence, and their authority, nearly always, served to curb my untamed and immature desires.

One of the things that I learned from them — an idea or a value judgment that was later underscored by my teachers — was that of “delayed gratification”. “Don’t eat it all”, was a common refrain, “leave some for later.” Initially, to my mind, such a statement used to annoy me. “Why can’t I eat it all now,” would be my thought, “especially after I waited so very long to get it?”

I learned to manage my personal desires within the context of being raised with a sibling, and while learning to socialize with my fellow students in school, who were all unique in their own right and who entertained their own hopes and dreams. I came to understand the wisdom of sharing — of “give and take”, and of how to navigate the fine line between the importance of my own individuality and that of the collective. It is, indeed, an art — a delicate dance, as it were — between my priorities and that of the group within which I found myself.

Such realities, which I learned through osmosis, revealed other strictures to what I wanted — guardrails against my unbridled passions. The learning processes were often not easy, but the lessons learned proved their value in the many and varied relationships which I have had later in life, since my youth, as a responsible member of a family, in my friendships, within my church affiliations, as an employee, as a spouse, and as a citizen.

The Good Book states that nobody lives to self or dies to self. It also advocates the loving of one’s neighbour as one’s self — expanding the notion of who one’s neighbour is to include those individuals who do not look and sound the same as we do, who do not always share our points of view, and who we might have very good reasons not to like.

The story of The Good Samaritan, which juxtaposed the lives of two individuals from different religious and ethnic beliefs, outlines what our response should always be to such individuals in times when they are most in need. This can be done without compromising our own values. Also, The Good Book goes a step further to enjoin us to love our enemies, of course, without being stupid about the threats that they pose.

This should be done in the hope of changing the jangling discords of human discourse, which such relationships tend to bring, towards a much higher level, akin to the sort of dialogue which is inspired by The Divine. For many in this nation who profess Christianity it is a virtue that they, woefully, lack.

All of what was just outlined by me might, to some, sound like the principles of the political ideology of liberal democracy, especially as it is being advocated in the United States, if not in practice, then at the very least, in principle. Such a situational awareness as touted by The Good Book is universal in nature in more ways than one, if we really think about it, cutting across cultures and across creeds. Such individuals as former African American slaves Sojourner Truth, Fredrick Douglass and Booker T. Washington come to mind, along with such Civil Rights icons as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the late, highly esteemed Congressman John Lewis.

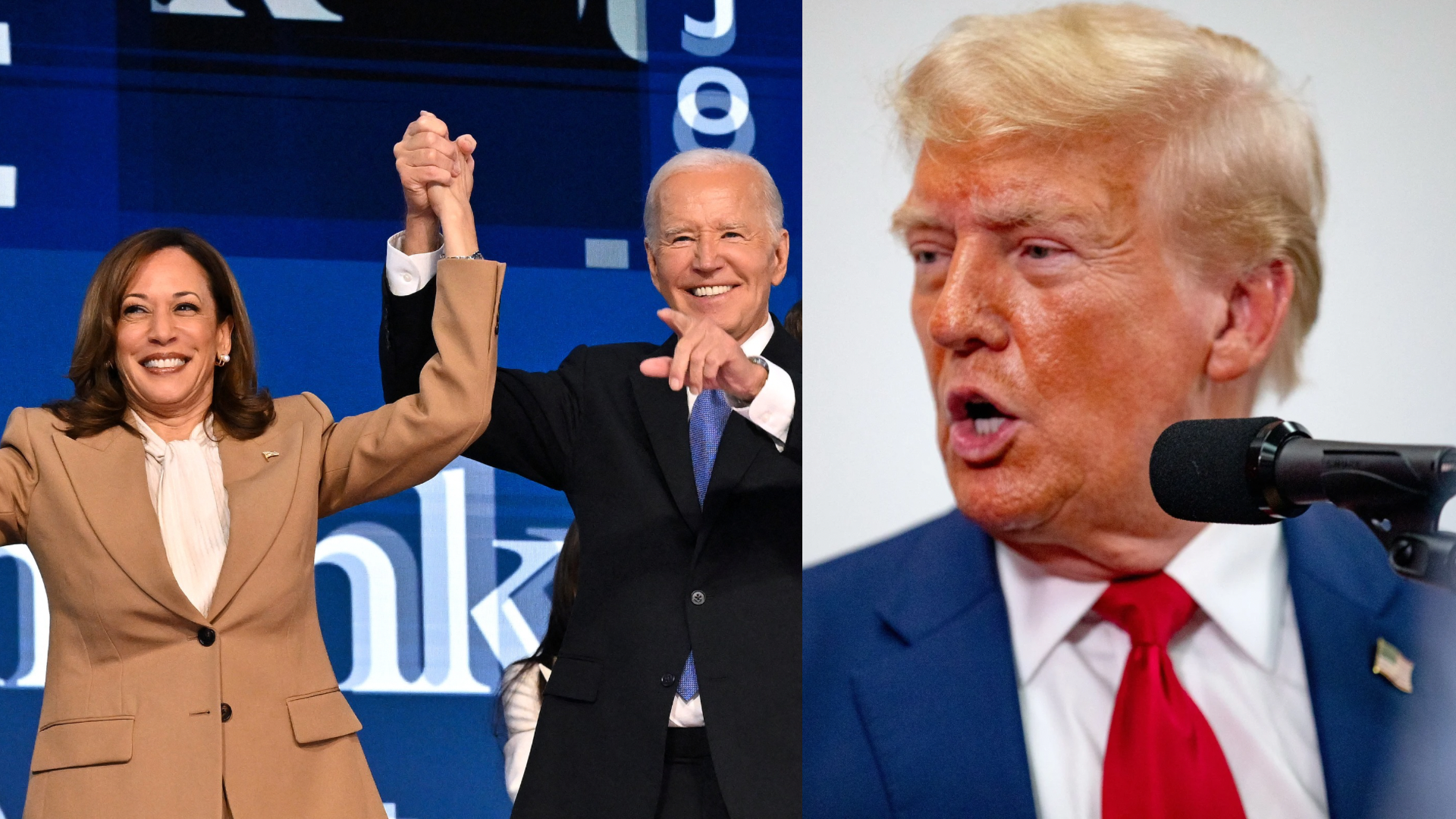

Outside of the American context I also think of Leo Tolstoy of Russia, Mahatma Gandhi of India, and Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela of South Africa. They all reflected the light of this flame of goodness within difficult times of political darkness. These individuals, and so many others who shaped my thinking and my personality, accompanied me in spirit when I cast my vote recently in the process of early voting. They helped me to define what I want out of this election.

I want the winner of this election to assure me, regardless of whether I will get some or most of the other things that I want out of this election cycle or not, that I will have the freedom to vote again in four years’ time, and every four years after that. Will I always have a voice in the affairs of this country — how it will be run? I pay my taxes, and I do my best daily to obey the laws of the land. I also want this right for all people, of all races, male and female, for rich and poor alike — whether they are Democrats, Republicans or Independents.

This is what I want for Christmas: In this election I want to be assured that, regardless of whether I will get some or most of the other things that I want out of this election cycle or not, that the U.S. Constitution, and every detail contained within it, will continue to be treated as the supreme law of the land, with its principles revered by all. When, at the swearing-in ceremony at the inauguration on January 20, 2025, next year, when the hand of the elected is raised to take the oath, that he will mean every single word, uttered below:

“I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

There was talk, by Mr Trump of suspending the U.S. Constitution and, if this is true, it is a matter of grave concern for me. It is not a perfect document, by any means, and it is not the same thing as The Good Book which inspires my faith, but it is what I signed up for and this is all that we have. Hence, I do not think that I am asking for too much of the President-elect.

The document provides the framework and the playing field for all of the political games that we play, with the various issues at stake and the vigorous debates that ensue because of them. Without it, we would cease to exist as a nation — as a democratic people.

In this election I want to be assured that, regardless of whether I will get some or most of the other things that I want out of this election cycle or not, that everyone will continue to have freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom to practice whatever religion they profess, remembering that not all of the nation’s founders and the framers of the Constitution were Christians. In fact, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison were deists, meaning that although they believed in the existence of a supreme being, that their god does not intervene in the universe. Jefferson did not believe that Jesus was deity and neither did Benjamin Franklin.

Noted historian, Jon Meacham, in his book, American Gospel – God, The Founding Fathers, And The Making Of A Nation, indicated that Jefferson and Madison fought for religious tolerance enshrined in law to protect all religions including Jew and Gentile, Christian, Muslim, Hindu and infidel of every denomination. Again, Meacham wrote, citing historical primary sources:

“The nation’s religious identity — or codified lack thereof — played a role in foreign policy. In the waters off Tripoli, pirates were making sport of American shipping near the Barbary Coast in the 1790s. Toward the end of his second term, Washington sent Joel Barlow, the diplomat-poet, to Tripoli to settle matters, and the resulting treaty, finished after Washington left office, bought a few years of peace. An interesting element of this long-ago document lies in Article 11, which reads,

‘As the government of the United States of America is not in any Sense founded on the Christian Religion — as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen, — and as the said States never have entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mehomitan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of harmony existing between the two countries.’ The Senate ratified the treaty at the recommendation of President John Adams.”

These are all that I want for Christmas this year, after election day. These, for me, are all non-negotiable. These should help to foster and to maintain peace and harmony in the country. These, for me, are all worth fighting for. On these matters I shall give no quarter.