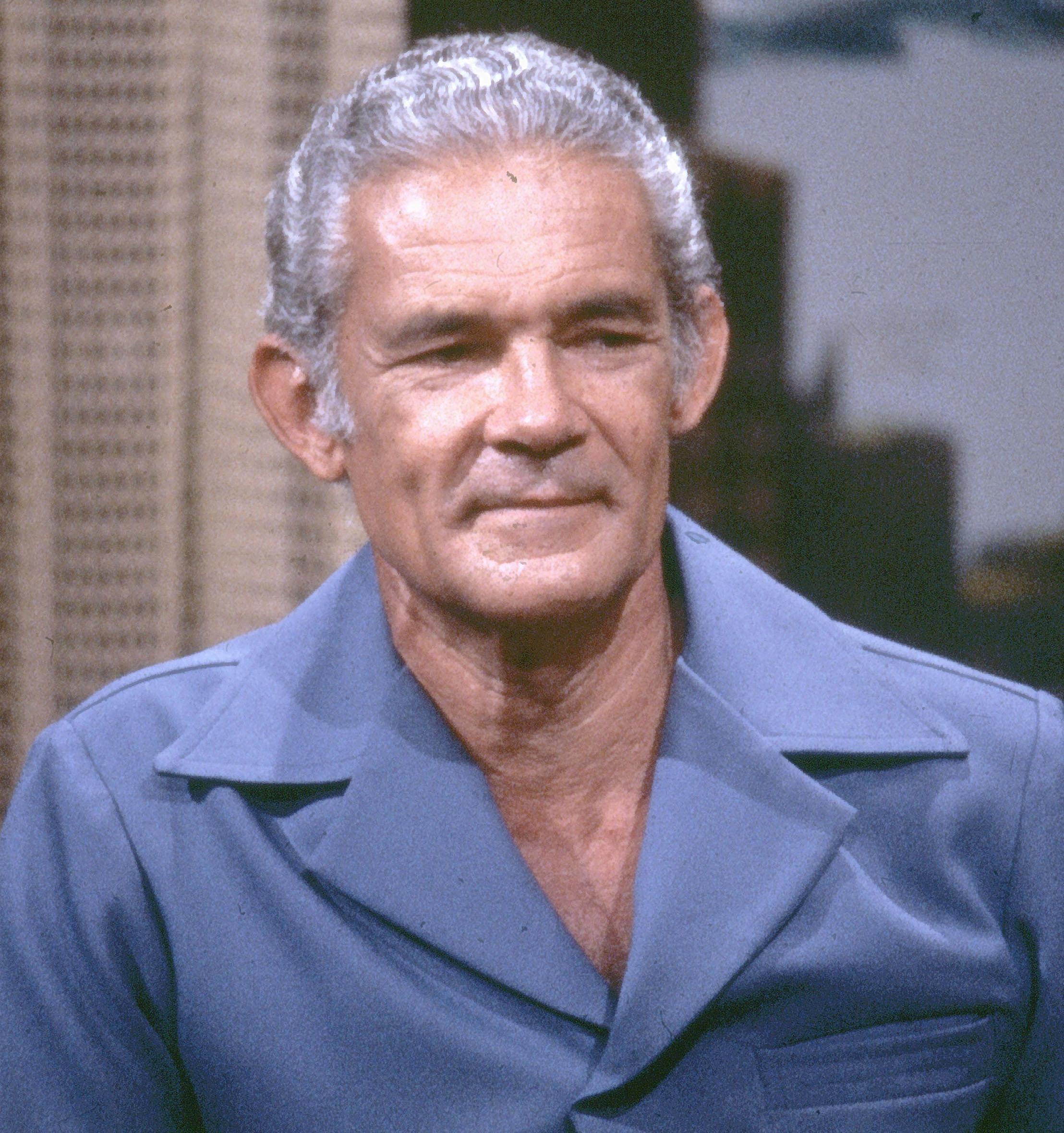

A recent interview done by Professor Anthony Bogues on Michael Manley’s centenary and entitled “Decolonizing Jamaica”, raised a number of interesting questions about the trajectory of our country’s future. As someone who has spent the last 30 years living abroad, it invoked a curiosity that caused me to research and reflect on Jamaica’s model of development. To get a good sense of Michael Manley’s genesis in public life I started with Professor Rex Nettleford’s edited version of Manley and the New Jamaica, depicting Norman Manley’s 30 years in public life.

What perhaps was etched in my thoughts was what the book portrayed, a collection of NW’s speeches that came to represent the touchstone of how as a people we should go about building a nation and shaping a new society from a decadent colonial past. In the 10 or more years following Norman Manley’s retirement, it was his son, Michael Manley, who took up the cudgel of leadership to continue the task of redefining the Jamaican polity through a philosophy of change.

The younger Manley attempted to forge this nascent development in the crucible of a turbulent and ideologically divisive environment, where local and international forces were at play to trump any attempt at continuing the veritable post-colonial transformation that began with the Sam Sharpe Uprising in the Christmas of 1831.

That struggle — for those who gloss over its significance — was about social justice, equality, self-reliance and the politics of change. That, too, was what Nanny represented in leading the Maroon Wars during the 1720s to 30s, manifested less in her military prowess, but more in its significance, which should never be lost on us, that her struggle was also about social justice, equality, self-reliance and the politics of change.

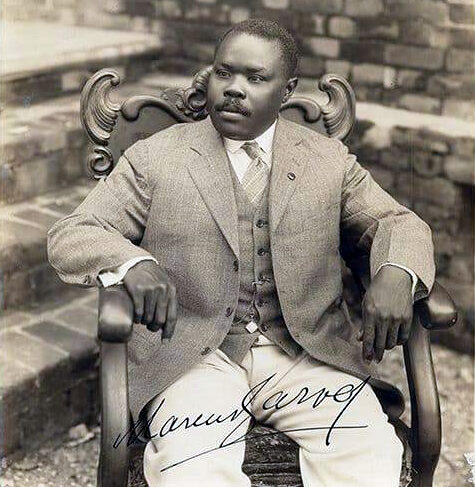

National heroes Paul Bogle, George William Gordon, Marcus Garvey, Norman Manley, and Sir Alexander Bustamante, one could argue, never accomplished the task they set out to accomplish; however, in the context of our own history we have paid the highest homage to them because they all represented a common set of ideas — a philosophy if you wish — that broadly defined the framework of a new Jamaica underpinned by notions of social justice, equality, self-reliance and the politics of change.

As Michael Manley puts it in his book of The Politics of Change, there is the need for us to effect an activist role in forging ideals and principles to reshape politics and the human conditions to achieve social justice, equality and self-reliance.

Were we ever to remain a colonised nation we would have had our oppressors as our national heroes, and the people’s heroes would have been vilified, with the ideals of social justice, equality and self-reliance, poignantly empty sloganeering. Remarkably, Norman Manley and others were able to win political independence, but by far the most perverse resistance to change resides simply with what Franz Fanon called, the ‘psychopathology’ of slavery and colonialism. This is why Marcus Garvey exhorted us to ‘emancipate ourselves from mental slavery’, as he argued ‘none but ourselves can free our minds.’

That is precisely what Michael Manley attempted to do with every bit of energy in his 40 years in public life, whether through his Public Opinion columns, The Root of the Matter, or his remarkable transformation of trade unionism and industrial relations during his time with the National Workers’ Union, or his two terms as Prime Minister. It is in that period of public service, between 1972 and 1975 and 1976 and 1980, that we have effectively drowned in the white noise of political gamesmanship and blurred the lines on that continuum between the struggles of our national heroes and Michael Manley’s mission in the post-Independence period.

In this the centennial year of Manley’s birth, we owe it to history and its consequences to do more than celebrate his remarkable efforts; we must see it as the bump of a revival to renew our people’s commitment and resilience to the cause for which Manley dedicated his life. Michael Manley belonged irreducibly to his time, for any attempt to diminish the philosophical sensibilities that honed the policies and programmes he attempted to introduce during his tenure as Prime Minister throughout the 1970s and early 1990s would represent a grave travesty to our forebears, and a blight on the country’s future.

Michael Manley has therefore to be located in the historical traditions where social justice, equality, self-reliance and the politics of change have defined who are our national heroes. For it is the ‘human condition’ more than economics that must define the development of a post-colonial society. The people made that abundantly clear in 1972 despite the continued economic growth, started during the Norman Manley regimes of 1955 and 1959, and continued throughout the 1960s. To parody former US President, Bill Clinton, “It is the social condition, stupid!” and not the economy in which we must anchor our development model.

This country would have been far worse today had Michael Manley not introduced a raft of social programmes, including free education; a national minimum wage; the removal of the bastardy act; the maternity leave law; equal pay for equal work; JAMAL, Project Land Lease; and formed the National Housing Trust, among others. Think about it; those were the most consequential changes made in post-Independence to redress what Garvey and Fanon saw as the post-traumatic slave syndrome. To misunderstand this is to misunderstand the true meaning and purpose of emancipation and the struggles of our National Heroes.

The meaning and purpose of our history are inextricably linked to a change in the human condition. We remain a society in crisis, as Manley said back in 1971, because “We have failed to recognise the primacy of the human element in what we do.”

We simply cannot celebrate, and genuinely so, the work of our national heroes, and in the same breath berate Manley’s attempt to change the human conditions. Unless, of course, our answer is in the affirmative to the questions posed by Manley in his May 12, 1976 budget presentation:

“But anybody who looked at the condition of the Jamaican human being after three hundred years of colonialism was bound to ask the question: Can this system, operating by its principles, by its laws of conduct, really create the condition of universal justice that must be the aspiration of all decent human beings?”

Manley argued, in The Politics of Change, that the restructuring of a post-colonial economy rests on “a set of economic objectives as being fundamental to the building of a just society,” and the first of which was ‘the growth of the economy.’ He went on to say that “where the commitment is to social justice, economic activity must serve the needs and interests of the whole social group…” and that it is “obviously important to maintain a substantial rate of growth…”

The performance of the economy between 1972 and 1976 demonstrated his commitment to fulfilling that objective. During the period 1972-76, GDP per capita showed an annual growth rate of 22.75% in 1974 and 18.74% in 1975, after that the numbers went south. Unemployment was 22.9% in 1972, 20.4% in 1975 and 25.9% in 1981.

The increase in average wages rose by 135% between 1970 and 1975 but plummeted to 55% between 1975 and 1980, while the average gross profit moved from 86% between 1970 and 1975, and 120% between 1975 and 1980 and 160% between 1980 and 1985. The tax burden on householders shifted from 23% in 1980 to 27% in 1985, while corporate taxes fell from 19% to 14% between 1980 and 1985.

I have separated 1972 to 1975 from 1976 to 1980 because things went south after that to turn back Manley’s efforts at continuing the post-colonial struggle of our National Heroes.

Somewhere in the US State Department I am sure resides the explanation as to what factors and forces conspired to trump Manley’s economic and social transformation programme, because Jamaica, unlike Singapore, was too close to the North.